Maria Arlamovsky's Future Baby questions and reflects on the options and bounderies of reproductive medicine.

I assume that many aspects of reproductive medicine and issues associated with the subject only emerged during the course

of your research, so it was also a voyage of discovery for you. What questions originally prompted you to embark upon this

voyage?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: I was interested in a variety of questions about this subject. In the foreground was clearly the fact that I am myself a

mother and also an adoptive and foster mother. As a foster mother I frequently attend training courses and undergo supervision,

and that often brings me in contact with social parents who would prefer to forget the biological aspect of parenthood for

the children they did not give birth to themselves, so that they can live within the usual pattern of father, mother and child.

I think the whole issue is problematic, because in the background there are shadow parents without whom it wouldn't have been

possible for people who can't give birth to children themselves to have a child. You have to respect them, because the child

is a part of those shadow parents. I wanted to take a closer look at the issue of shadow parenthood, which is so often suppressed,

especially regarding the shadow mothers – by which I mean egg donors and surrogate mothers.

Since the debates revolve to such a large extent around pregnancy and people who so much want to be parents, the film could

also have been called Future Mum. But you chose the title Future Baby, clearly placing the emphasis on the living being created

by the methods you present here. Is too little thought given to the child that ensues, in your view?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: The baby actually becomes an object like a car or a house. Anyone who pays enough money can have a child created. In the

places where fertility tourism flourishes, the legal restrictions tend to be relaxed. The idea of an optimised child isn't

new. We all make an effort to optimise our children, by doing things like sending them to bilingual kindergartens or ballet

lessons. But now I can apply this desire for optimisation at increasingly early stages; soon I'll be able to choose from five

embryos the most intelligent or the blondest baby. It's becoming more and more technological. It's no longer the case that

I look at my child's talents and attempt to promote them. Soon I will be able to stipulate in advance what kind of child I

want. We still have some way to go before we get to that stage, but the conceptual structure is already being set up. I got

the impression that the point isn't always people's desire to be parents: in many cases the issue is rooted in social convention.

Although I don't make this an explicit subject of Future Baby, I do touch upon the issue. Because all the women in my film are having babies for their husbands. Whether they are having

a child by means of a donor cell or a surrogate mother, they explicitly point out that their husbands’ DNA is still involved.

I also wanted to allow the social pressure to be felt in this film. In Future Baby I wanted to bring together aspects of reproductive medicine which are generally kept separate. After all, the industry doesn't

make it clear to us what a woman has to go through to be an egg donor, or how sad a surrogate mother looks after giving birth.

If I don't have to confront those images, showing what other women have to do in order for me to fulfil my desire to have

children, then it's easier for me to hand over my cash in payment for their services.

The technology is one aspect, and the legal framework is certainly another. Your research and the process of filming must

have brought you into contact with the legal situation in various countries. Which countries have liberal regulations that

permit a lot of options and developments in this area?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: Anyone who takes a closer look at fertility tourism quickly establishes where different things are possible. There are maps,

in a constant state of flux, that you have to study. We had decided to explore the subject of surrogate motherhood, but for

a long time we didn't know where we would be able to film. When we started our research India was becoming the boom destination,

because affordable surrogate motherhood was also possible there for homosexual couples. Then the situation changed, like with

adoptions: if something works too well, it becomes so popular that it gets out of hand. One scandal is enough for the whole

thing to be halted. Then the entire circus moves to another country which happens to be open for business. After India focus

shifted to Thailand, until a few individual cases there are also put an end to the business. By the time we were ready to

shoot the film Mexico had become the new destination, with its liberal laws, and everyone rushed there. We ended up in some

countries more or less by chance, you could say. California is one place you can't really avoid; ever since the Reagan era

it has been characterized by very liberal policies with generous investment in research, because the commercial potential

of bio policies was recognized at an early stage. After Franco's dictatorship very liberal laws were passed in Spain, and

that country maintains a predominant role in research within Europe. Israel is the country with the densest networks of IVF

clinics. There women over the age of 25 resort to IVF if they don't become pregnant after trying for six months, because the

state covers the cost of the IVF procedure for the first three children. So there's a very strong government policy underpinning

that situation.

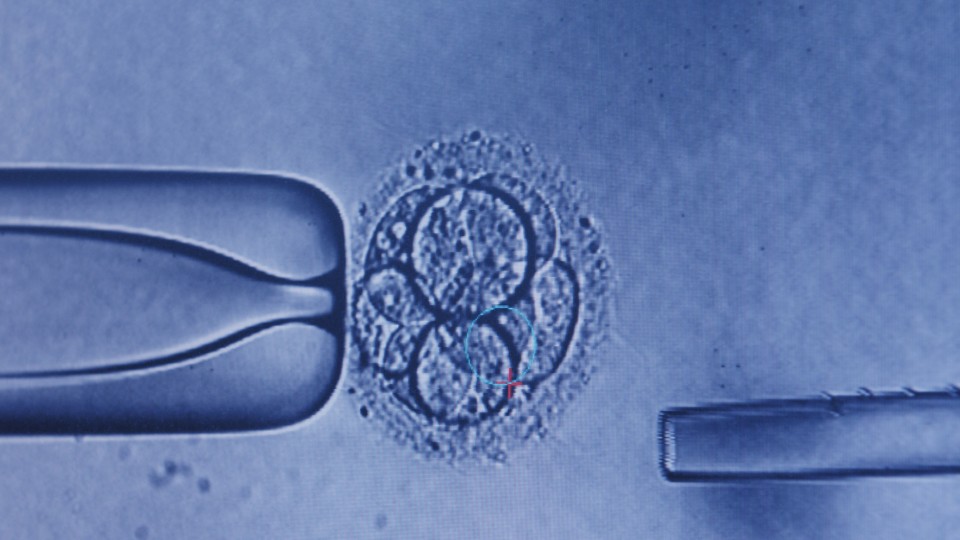

You filmed in operating theatres and in doctors’ surgeries. Here too the question must arise: how far can I go, how far

do I want to go? When you push back the boundaries in terms of visual conventions, is that also a way of bringing it home

to viewers that borders are being explored within the subject of your film?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: I believe it's important to create harsh images and to confront people with pictures that are difficult to digest, because

then you can't escape the issues. When something is given concrete form as an image, it's harder for me to ignore it. And

it's also a relief to have images that pin down such an abstract subject. It was clear from the very outset that we wanted

to show these really harsh images. And that we wanted the camera perspective from above, conveying some sense of the people

being pinned down. Our camera concept, which I developed together with my son Sebastian, the cameraman on this film, actually

changed with regard to the use of hand cameras. Originally we wanted to be closer to the people. But using a hand camera requires

time, closeness and intimacy, and we weren't in contact with the people involved for long enough, so finally we decided not

to approach the individuals so closely.

In Future Baby you try to make it clear that current reproductive medicine also entails invasive procedures for the women

involved. Why is this aspect of particular importance to you?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: The way I perceive it, reproductive medicine – like contraception – actually constitutes an invasion of the woman's

body, in a certain sense. People act as though giving a woman such powerful hormones doesn't have any consequences. Future Baby reveals that it's necessary to give a general anesthetic in order to remove egg cells, and the procedure involves hormonal

overstimulation so that 20 egg cells can be removed at one time, for example. I wanted to show that a woman who is too old

to have a child using her own egg cells needs a younger woman in order to do so. But why didn’t the older woman think

of having children when she was younger? Because we live in a society that doesn't create the conditions for both courses

of action – having children and making a career – let alone ensure that all of us, men and women, develop the desire

to have children. Society pushes women towards having a career, and then it's their responsibility to live with the consequences.

I perceive that as an exploitation of a woman's body, even before the subject of surrogate motherhood comes up. I really must

emphasize here that I'm not opposed to these methods; I simply want to help raise awareness that there must be some arrangement

between equals, an arrangement that everyone agrees on, involving the partners necessary for reproductive medicine. I can't

take egg cells from a woman who hasn't been fully informed about the situation in order to place them in the body of another

woman who pays a lot of money for the procedure. That's got nothing to do with medicine any more. And that's my point. I'm

not trying to turn back the wheel. I would like better regulation and efforts to raise awareness that there are social mothers

and biological mothers, or biological egg donors if the word "mother" is to be avoided.

The initial focus of your film is on parents who want to have children. That makes it all the more interesting to discover

the perspective of Noa and Ruth – the only mother and child in the film where the child is an adult – for whom it

would be so important to get to know her father.

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: In making this film I worked with a lot of people who were not conceived in traditional style. Noa is the only one who features

in the film, because it emerged that this is a powerful subject for the people involved, and I'm glad the material we filmed

could raise this issue, which might become a TV documentary itself. Of the people we talked to, Noa most powerfully expressed

the issue here, which is that it's not right when you don't know your genetic origin. Even if genetic background isn't everything,

the children must have the right to look for reflections of themselves and know where they come from. This is clearly an enormous

need, and it can't simply be ignored. Up to now we've used the term patchwork families to include stepmothers and stepfathers.

But now this repertoire of roles is becoming more extensive; we have social mothers and fathers, donating mothers and biological

mothers… As a society we have to recognize this and apply that understanding somewhere. At some point in the future we

will see grown donor children standing up and demanding their rights.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

April 2016

Translation: Charles Osborne

I assume that many aspects of reproductive medicine and issues associated with the subject only emerged during the course

of your research, so it was also a voyage of discovery for you. What questions originally prompted you to embark upon this

voyage?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: I was interested in a variety of questions about this subject. In the foreground was clearly the fact that I am myself a

mother and also an adoptive and foster mother. As a foster mother I frequently attend training courses and undergo supervision,

and that often brings me in contact with social parents who would prefer to forget the biological aspect of parenthood for

the children they did not give birth to themselves, so that they can live within the usual pattern of father, mother and child.

I think the whole issue is problematic, because in the background there are shadow parents without whom it wouldn't have been

possible for people who can't give birth to children themselves to have a child. You have to respect them, because the child

is a part of those shadow parents. I wanted to take a closer look at the issue of shadow parenthood, which is so often suppressed,

especially regarding the shadow mothers – by which I mean egg donors and surrogate mothers.

Since the debates revolve to such a large extent around pregnancy and people who so much want to be parents, the film could

also have been called Future Mum. But you chose the title Future Baby, clearly placing the emphasis on the living being created

by the methods you present here. Is too little thought given to the child that ensues, in your view?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: The baby actually becomes an object like a car or a house. Anyone who pays enough money can have a child created. In the

places where fertility tourism flourishes, the legal restrictions tend to be relaxed. The idea of an optimised child isn't

new. We all make an effort to optimise our children, by doing things like sending them to bilingual kindergartens or ballet

lessons. But now I can apply this desire for optimisation at increasingly early stages; soon I'll be able to choose from five

embryos the most intelligent or the blondest baby. It's becoming more and more technological. It's no longer the case that

I look at my child's talents and attempt to promote them. Soon I will be able to stipulate in advance what kind of child I

want. We still have some way to go before we get to that stage, but the conceptual structure is already being set up. I got

the impression that the point isn't always people's desire to be parents: in many cases the issue is rooted in social convention.

Although I don't make this an explicit subject of Future Baby, I do touch upon the issue. Because all the women in my film are having babies for their husbands. Whether they are having

a child by means of a donor cell or a surrogate mother, they explicitly point out that their husbands’ DNA is still involved.

I also wanted to allow the social pressure to be felt in this film. In Future Baby I wanted to bring together aspects of reproductive medicine which are generally kept separate. After all, the industry doesn't

make it clear to us what a woman has to go through to be an egg donor, or how sad a surrogate mother looks after giving birth.

If I don't have to confront those images, showing what other women have to do in order for me to fulfil my desire to have

children, then it's easier for me to hand over my cash in payment for their services.

The technology is one aspect, and the legal framework is certainly another. Your research and the process of filming must

have brought you into contact with the legal situation in various countries. Which countries have liberal regulations that

permit a lot of options and developments in this area?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: Anyone who takes a closer look at fertility tourism quickly establishes where different things are possible. There are maps,

in a constant state of flux, that you have to study. We had decided to explore the subject of surrogate motherhood, but for

a long time we didn't know where we would be able to film. When we started our research India was becoming the boom destination,

because affordable surrogate motherhood was also possible there for homosexual couples. Then the situation changed, like with

adoptions: if something works too well, it becomes so popular that it gets out of hand. One scandal is enough for the whole

thing to be halted. Then the entire circus moves to another country which happens to be open for business. After India focus

shifted to Thailand, until a few individual cases there are also put an end to the business. By the time we were ready to

shoot the film Mexico had become the new destination, with its liberal laws, and everyone rushed there. We ended up in some

countries more or less by chance, you could say. California is one place you can't really avoid; ever since the Reagan era

it has been characterized by very liberal policies with generous investment in research, because the commercial potential

of bio policies was recognized at an early stage. After Franco's dictatorship very liberal laws were passed in Spain, and

that country maintains a predominant role in research within Europe. Israel is the country with the densest networks of IVF

clinics. There women over the age of 25 resort to IVF if they don't become pregnant after trying for six months, because the

state covers the cost of the IVF procedure for the first three children. So there's a very strong government policy underpinning

that situation.

You filmed in operating theatres and in doctors’ surgeries. Here too the question must arise: how far can I go, how far

do I want to go? When you push back the boundaries in terms of visual conventions, is that also a way of bringing it home

to viewers that borders are being explored within the subject of your film?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: I believe it's important to create harsh images and to confront people with pictures that are difficult to digest, because

then you can't escape the issues. When something is given concrete form as an image, it's harder for me to ignore it. And

it's also a relief to have images that pin down such an abstract subject. It was clear from the very outset that we wanted

to show these really harsh images. And that we wanted the camera perspective from above, conveying some sense of the people

being pinned down. Our camera concept, which I developed together with my son Sebastian, the cameraman on this film, actually

changed with regard to the use of hand cameras. Originally we wanted to be closer to the people. But using a hand camera requires

time, closeness and intimacy, and we weren't in contact with the people involved for long enough, so finally we decided not

to approach the individuals so closely.

In Future Baby you try to make it clear that current reproductive medicine also entails invasive procedures for the women

involved. Why is this aspect of particular importance to you?

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: The way I perceive it, reproductive medicine – like contraception – actually constitutes an invasion of the woman's

body, in a certain sense. People act as though giving a woman such powerful hormones doesn't have any consequences. Future Baby reveals that it's necessary to give a general anesthetic in order to remove egg cells, and the procedure involves hormonal

overstimulation so that 20 egg cells can be removed at one time, for example. I wanted to show that a woman who is too old

to have a child using her own egg cells needs a younger woman in order to do so. But why didn’t the older woman think

of having children when she was younger? Because we live in a society that doesn't create the conditions for both courses

of action – having children and making a career – let alone ensure that all of us, men and women, develop the desire

to have children. Society pushes women towards having a career, and then it's their responsibility to live with the consequences.

I perceive that as an exploitation of a woman's body, even before the subject of surrogate motherhood comes up. I really must

emphasize here that I'm not opposed to these methods; I simply want to help raise awareness that there must be some arrangement

between equals, an arrangement that everyone agrees on, involving the partners necessary for reproductive medicine. I can't

take egg cells from a woman who hasn't been fully informed about the situation in order to place them in the body of another

woman who pays a lot of money for the procedure. That's got nothing to do with medicine any more. And that's my point. I'm

not trying to turn back the wheel. I would like better regulation and efforts to raise awareness that there are social mothers

and biological mothers, or biological egg donors if the word "mother" is to be avoided.

The initial focus of your film is on parents who want to have children. That makes it all the more interesting to discover

the perspective of Noa and Ruth – the only mother and child in the film where the child is an adult – for whom it

would be so important to get to know her father.

MARIA ARLAMOVSKY: In making this film I worked with a lot of people who were not conceived in traditional style. Noa is the only one who features

in the film, because it emerged that this is a powerful subject for the people involved, and I'm glad the material we filmed

could raise this issue, which might become a TV documentary itself. Of the people we talked to, Noa most powerfully expressed

the issue here, which is that it's not right when you don't know your genetic origin. Even if genetic background isn't everything,

the children must have the right to look for reflections of themselves and know where they come from. This is clearly an enormous

need, and it can't simply be ignored. Up to now we've used the term patchwork families to include stepmothers and stepfathers.

But now this repertoire of roles is becoming more extensive; we have social mothers and fathers, donating mothers and biological

mothers… As a society we have to recognize this and apply that understanding somewhere. At some point in the future we

will see grown donor children standing up and demanding their rights.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

April 2016

Translation: Charles Osborne