The father of Hermann Gebirtig (his name is the Yiddish pronunciation of the German word gebürtig, "born in" or "native of") was murdered in a concentration camp. As was Danny Demant's father. And the two never had the chance to meet.

Susanne Ressel's father, a resistance fighter with the Communists, survived his time in a camp, then succumbed 40 years later as an indirect result. Konrad Sach's father terrorized a concentration camp as its doctor, for which he was hung in Nuremberg as a war criminal. Nothing is said about the father of Christiane Kalteisen- he possibly played a passive role in the regime's crimes. As a doctor, Kalteisen encounters death every day, and her sole association with Auschwitz is that it is located in Poland. This is not due to ignorance- she merely lives firmly in the present. Circumstance had determined 40 years ago that some people would be victims and others perpetrators. And circumstances would bring these five people together 40 years later, in Vienna in the 1980s, after which they stumble along with the burdens of their respective personal pasts before finding themselves in the end. Robert Schindel's much-noted novel Gebürtig portrays the significance of the past and one's origins, inherited guilt and successfully dealing with the present within a complex web of relationships.

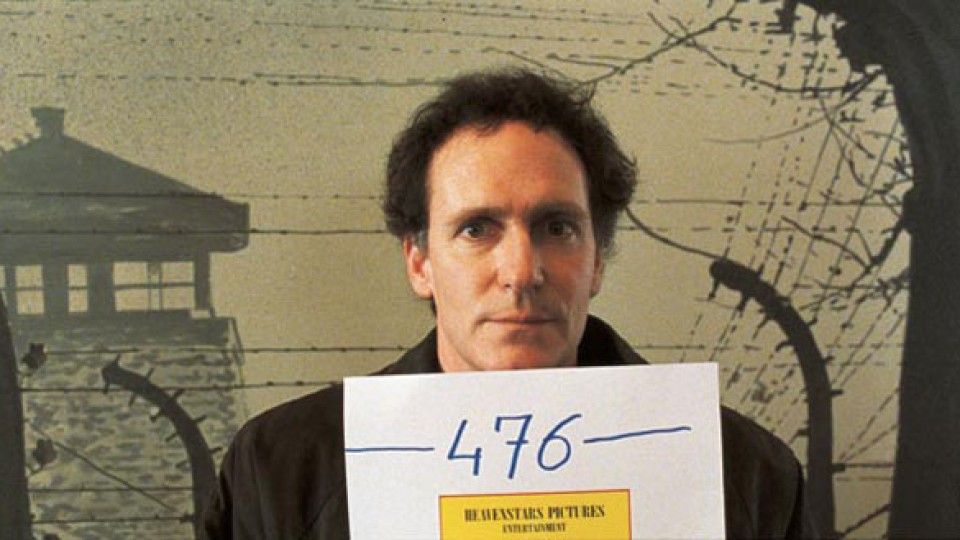

The author adapted his novel for the screen and directed the film version together with Lukas Stepanik. The protagonist is Hermann Gebirtig (Peter Simonischek), the son of Jewish parents who died in a concentration camp. After the war's end he emigrated to New York and enjoyed a successful career as a composer of musicals and hit songs. By making a firm decision to turn his back on Vienna forever, the city of his childhood which had also taken everything from him, he found in the same way as the others, all of them members of the post-war generation, a method of dealing with the burdens of the past. This works until a certain event or a chance encounter suddenly confronts them with the past anew, and with themselves.

Cautious Reconciliation "At the same time, it is neither," insist both co-directors, "a film about the Holocaust nor is it meant to help people come to terms with the past- it is about dealing with the present. The only thing that can be managed is how the past affects the present and how people cope with that today. Our intention was to show that these are human beings who, due to their specific origins, are bound to either the perpetrators or the victims, and through no doing of their own." In Gebirtig, a complex web of personalities replaces the polarity of victims and perpetrators, making clear the variety of personal fates and rearranging the bonds between its characters, whose lives are as different as they are alike. In the end, this provides opportunities for cautious reconciliation. Vienna in the period just after the affair involving then president Kurt Waldheim provides a historical context in which two threads play out: a film within the film, shot at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, in which Danny Demant plays the Jewish victim of a camp doctor, and another showing the characters' daydreams interspersed with actual memories.

"In a linear narrative," claimed Lukas Stepanik, "each character could serve as the basis of a story. The challenge of the adaptation, and its most interesting aspect, was maintaining the wealth of material in the novel. In the film the various elements are thoroughly rearranged and restructured." A trio of screenwriters, Stefan Troller, Robert Schindel and Lukas Stepanik, produced a total of eight versions of the script, linked various threads which never coincide in the novel, and stick to the narrator's role. Danny Demant (August Zirner) plays a dual role in the film, both an actor and cabaret performer and the distant observer. His ironic off-camera commentary sums up and overlaps with the story, at the same time underlining the pointed dialog and the literary character of the material. The narrator's humorous tone prevents things from slipping into excessive drama.

"In my opinion," claimed Robert Schindel, "this subject cannot be addressed without a certain amount of humor, and even laughter. Anyway, I wouldn't be able to write a book or shoot a film without this lubricant, which makes it easier for these unpleasant facts to enter into the consciousness, or the soul." Open Dialogue By the 1980s Hermann Gebirtig, one of the last remaining contemporaries, identifies Pointner, whose nickname was "Skull-Breaker" during his infamous career in the Ebensee camp, thereby gaining for himself and the other victims a shred of redress. Susanne convinces him to leave his American exile and come to Vienna and testify, to the country, as he puts it, "which sees itself as a victim in such a way that there's hardly anything left for those the victim victimized." But when he reaches the place where he spent his childhood, the bitterness he has cultivated over the years is no match for the wave of emotions which suddenly overcomes him.

"We've felt sorry for ourselves for too long" is the conclusion reached by both Konrad, the son of a murderer, and Gebirtig, a victim. Author Robert Schindel, having been born in 1944 to Jewish parents, belongs in a sense to both the survivors and the post-war generation. In contrast to Hermann Gebirtig he remained in the city of his childhood although many of his relatives fell victim to the Nazi regime. He does not view the composer as his alter ego. "The conclusions Gebirtig has drawn from his life," according to Schindel, "are those of a literary figure. I'm not very good at hating- I never have been. And I can't accept a reconciliation in the name of my family. However I can make a personal attempt to settle things for myself by choosing people for an open dialog- people who themselves or whose parents were Nazis or passively participated, who were more actively involved or just looked away. I can attempt to show that they bear some responsibility for the victims' descendants, so that everyone can live here without fear."

Karin Schiefer (2002)