Creating relevant films collectively was the impetus for young filmmakers from Kiev to found the Tabor production lab more

than ten years ago. For Yelizaveta Smith, Alina Gorlova and Simon Mosgovyi, creating images together to counter the inescapable

reality of chaos and destruction in the sudden state of war became an existential strategy. MILITANTROPOS explores the double nature that military violence turns people into, allowing a profound collective portrait and a narrative

to emerge in the turmoil of loss and solidarity, which brings together meaning where solid ground seems to shatter.

Let’s start about finding out a bit about your Kyiv-based production company TABOR LTD. What motivated you to found your own

company, and how would you describe its profile?

ALINA GORLOVA: We founded the company eleven years ago. The idea to establish this company came up when we graduated from film school. We

quickly realized that it would be difficult to make creative, author-driven films given the market and the production landscape.

We decided as a team of authors and directors to found our own company with the goal to make our own films. We trained ourselves

in the film industry by doing. In 2016 Lisa’s film School Number 3 celebrated its premiere at the Berlinale – that was the year when we started to explore the international film industry and

to learn how co-productions work.

YELISAVETA SMITH: I’d like to add another point: the idea was not only to have a production company but also a collective of people who work

together. That’s our biggest achievement, since it really worked out for us. TABOR Production was founded by several directors,

but we also have great DoPs, an art department, a sound department ... All started in connection with the Revolution of Dignity

as we filmed at that moment. This collaboration over ten years transformed us as people and artists, as the influence on each

other was very strong. I consider it our biggest advantage to function as a collective.

ALINA GORLOVA: And the story of how our collaboration with Mischief Films in Vienna came about is particularly noteworthy. Very quickly after

the start of the full-scale invasion, the Austrian Ministry of Culture set up a fund for artists in Ukraine, which you could

apply for via a company or institution in Austria. An Austrian colleague put us in touch with Ralph Wieser and then there

was actually just a Zoom call, just to get to know each other. Ralph submitted the application on our behalf and transferred

the approved € 5,000 to us. That was the starting signal. Later on, when Arte joined the project through their Generation

Ukraine Initiative, Mischief Films was able to submit our project to the Austrian film funding institutions.

How many of you belong to the TABOR team?

ALINA GORLOVA: The core team consists of around ten people in charge of the operative tasks, decision-making, accounting, producing etc.

And there are a lot of people around us who are very often involved in our projects, such as

Simon.

SIMON MOZGOVYI: Yes, I’m actually one of the involved persons. They call me an adopted child.

In the word Militantropos, the title of your film, two concepts the soldier and the human being are fused into one. You

give a first written definition at the beginning of the film. Did you develop this concept on the basis of theoretical reflection

about this hybrid being?

YELISAVETA SMITH: At a certain point we understood how important it is to create meanings in this world of total chaos and destruction we’re

living in. Meanings that can serve as our base helping us realize, experience and understand the nature of war. In the past

eleven years of TABOR’s history almost all projects have been related to war. Alina, Simon, myself

we all collaborated as

directors, producers and editors of our respective films, most of them were about war. The aim of our collective project is

to go deep into the nature of war and try to understand how the human being is going through this experience. That’s how we

perceive this neologism, which was created by Maksym Nakonechnyi, who is a co-author of our script. It comes from two terms,

the Latin word miles for soldier and the Greek word anthrōpos for human being. The neologism is about how the human being

is changing within the war. In this context the three of us collaborated with Oleksandr Komarov, an Ukrainian philosopher

of our generation, who has been in the army for these last three years. His inner experience of going through war was a very

important contribution to our work.

Militantropos defines a hybrid being. Is it about a loss of identity? The creation of a new identity? Can you share your thoughts

on this term?

SIMON MOZGOVYI: I would not agree with the idea of loss of identity. It’s more about re-gaining identity rather than losing it. Of course,

war is a horrible event; we are in the middle of the war, and it was not our choice. But we can choose what we do with our

lives and how to stay human under these circumstances. It is more about taking action rather than about losing something.

I’m referring to the definition at the beginning of your film, which states “the chaos of war fractures the militantropos’s

sense of self.”

SIMON MOZGOVYI: Yes, it is about losing the common world that you had, but it doesn’t mean a loss of identity. I’d like to mention the ideas

of Viktor Frankl, the Austrian psychotherapist who survived the concentration camp during World War II. He says that the human

being can stand everything as long as they understand why. The essence of his ideas is about the fact that we have to know

why we are making certain choices. We can lose everything except the human being inside us. Personally, for me, it’s not about

losing the identity but about crystallizing it.

ALINA GORLOVA: I agree. Still, I think the question is very close to the idea we developed based on our own experience in the very beginning

of the full-scale invasion. One became very disoriented and fractured. In a sense, we also went through this process in the

film. In the very beginning we have quite painful and traumatic scenes. That’s how trauma works: Trauma fractures your memory,

also your identity and it’s very important for the individual, for society and for us as filmmakers to rearrange all the events

and build a narrative. When you’re going through this process I have a metaphor for it from making this film: We used documentary

scenes, tried to build a narrative out of them, to find meaning in what had happened to us, and in a way, to reconstruct the

human being.

How did the three of you team up together and develop a film concept based on these reflections?

YELISAVETA SMITH: The philosophical concept of MILITANTROPOS evolved while we were working on the film. It hasn’t been the theory first and

then the film. Both elements evolved hand in hand during the making of the film. We had been working so much in the field

of war and all of us dreamed of doing something else in our lives. But the full-scale invasion by Russia happened and we had

to change direction again.

SIMON MOZGOVYI: At the beginning of the Russian invasion, the process of filming was our inner way of existence, so as not to lose ourselves

and our ideas on why we had become filmmakers. It was our first impression, our first reflection, and then we connected with

each other and came to the conclusion that we wanted to create something collectively. We were aware that an individual experience

might not be as powerful and profound for exploring the core of war. We decided to make a collective project. We were several

directors and DoPs working in different groups, also switching roles and switching teams, but all the footage went in one

direction. After about six months of filming, we went through the material and started to develop the concept.

ALINA GORLOVA: When the full-scale invasion started, we, the core members of TABOR, were at different places. A part of the crew was in Kyiv,

Simon was near the frontline, Lisa and Viacheslav Tsvietkov, another DoP, were in central Ukraine. We were all separated from

each other. When we had calls, we realized that each crew was already filming something not on a large scale, but everyone

was volunteering and documenting at the same time. During the first weeks of the full-scale invasion, we had a group chat

and decided, "We’ll make a film.", since everyone had already started filming. That’s how it all began. From the very beginning,

our goal was to bear witness. Not many people had stayed in Kyiv, and it felt crucial to document what was happening to

capture the unfolding events, to preserve the atmosphere, and to record evidence of war crimes.

During which period were the images taken?

SIMON MOZGOVYI: We filmed from February 24, 2022, until the end of August 2024.

YELISAVETA SMITH: The editing process was already underway and we saw what needed to be added. In total, we had three DoPs, outstanding authors,

artists who cannot be easily found in Ukraine: Viacheslav Tsvietkov, Khrystyna Lizohub, Denys Melnyk. We needed them greatly

to work on this project. It was a very important collaboration for TABOR, it’s part of the mutual process within our collective

during which we form each other.

I imagine that bringing these images together required a long editing process. Was this process – I refer again to the title

of the film – also marked by a twofold vision and intention to create a balance within the narrative – a balance between army

life and private life, between the city and the countryside, the different seasons ...

YELISAVETA SMITH: It was based on two parts: the military and the civilians. How are humans going through this and making their decisions?

SIMON MOZGOVYI: We are talking about the human being in war, encompassing both civilian life and life in the midst of war. First, we collected

the images, and when we had a first rough cut, we discovered inner levels and forms. We started capturing nature, and we understood

that we wanted to have some extra character. One of them was the sky. We were trying to find out what unites all of us, the

way how these two worlds could be connected for the viewer. We decided to do it through the sky. It’s the same sky under which

children are playing below blossoming trees in the center of Kyiv and under which soldiers are working in the trenches. We

were filming the moon, the clouds

in order to find the visual language of this sky. And we built the structure of three

parts and defined the differences. The first part is narrated with a certain distance, while in the third part we move closer

and closer to our characters.

The sky is only one part; nature in general plays a crucial role in the film. Did you also want to show us how nature is wounded

by war, and at the same time, an element of continuity, changing with the seasons and offering a sense of stability, independent

of what is happening?

ALINA GORLOVA: Exactly. Nature is always there. During the hostilities and on the frontline, I heard soldiers talk about their experience.

When you are on the frontline and going through a dangerous situation, that puts you really close to death, you start noticing

very simple and beautiful things, mostly in nature – flowers in the grass or something like that. Awful things are about to

happen against the backdrop of a beautiful nature. Nature is always there and always beautiful whatever is going on.

I read the sky also as a metaphor of fate. You give us the very strong opening sequence with a grey cloudy sky which is slowly

merging into the smoke of a huge fire. Black birds on this cloudy sky that might be a sinister sign. How are you reading this

opening?

SIMON MOZGOVYI: We’re working with some highly symbolic elements in the film, trying to find a connection between the images we captured and

something we knew from Greek mythology or our folklore stories, something that connects the present and the past of human

history. Nature itself, such as thunder, storms and rain, was always an element for the human being to look at and relate

to. We put it in the film to help our viewers to consider it as relevant. The meanings that we find were not invented; they

were always with us.

YELISAVETA SMITH: Ukrainians have a strong connection to nature and to their land; it’s been like this for centuries, since this ground delivers

a lot of food. They work this ground not only out of a sense of duty, there’s a tradition and also a deep love for it. People

still grow food because they feel this inner need. It says a lot about our people. I feel this inside me, although I’ve never

worked the ground and although I’m a real city person, I feel this love inside myself. The relation to the ground is something

that unites all Ukrainians. I perceived this in villages in the countryside, no matter what – the war is there, the drones

are coming, the mines are in the ground, you still need to work on your land. For me, this is about resistance and love.

The camerawork is very sensitive, playing with distance and closeness and always choosing the adequate approach. Did you exchange

with your DoPs how to approach people? Did they tell you how they went through difficult moments of shooting?

YELISAVETA SMITH: In the very beginning of the full-scale invasion, we tried to keep our distance. This was a deliberate decision. The more

we filmed, we increasingly felt the urge to approach the people more closely. This was very challenging, since we had to deal

with a very high level of emotions. We were very much interested in the portraits, in the emotions. Observational documentation

usually happens in wide shots with a lot of people and that’s how you create a collective portrait. We realized that we wanted

to create a collective portrait based on close-ups of our protagonists. As for the work with our DoPs, it’s built on a very

long work relationship. I arrive at the location where we would like to film and I’m searching for the protagonists on the

field. I’m always looking for the most open people, who are ready to interact with us. As soon as we have the impression that

a person is not responding very much, we don’t film. That’s a rule all of us have been respecting. All of us were on the ground

all the time, there are only very rare moments in which they worked without us. Even during the editing process, we stayed

in contact with them, we showed them versions, discussed it with them. It was very important for us that they stayed inside

the creative process. When we asked them to do an additional shoot, they knew all the material.

Have you kept in mind very strong, memorable moments?

YELISAVETA SMITH: So many of them

...

ALINA GORLOVA: A very powerful experience was the stabilization point, where people are receiving first aid. Secondly, I’d mention a shoot

with young soldiers, I was very impressed by the combination of youth and war. They were very young, full of young energy,

they were fighting and felt very strong, motivated and not traumatized. They gave me an impression of teenagers who are doing

very essential things.

SIMON MOZGOVYI: I was very impressed by the combination of emotions. It was never only horrible events. It could be a combination of fear

and pride; it could even be love. Emotions reflect and affect me as much as they can. For example, the evacuation scene in

the Kharkiv regionmy homeland. It was the period of the second occupation in 2024; the place had been occupied for eight

months. We are in the middle of this chaos, and you learn about how people care. Most of the Ukrainians are worried about

the animals they havethe cats, the dogs, the cows. Lisa already talked about the ground connection. Most of the people refused

to leave their homes because they were planting something and didn’t want to leave that behind, or they didn’t want to leave

a dog or a cow, or they tried to rescue it. It’s so much about mixed feelings; it made me go inside the meaning of being human

under such conditions. You’re not thinking about yourself. Whenever you saw the cities burn, there were volunteers, police

officers, who were rescuing people and risking their lives by doing so. It was about fear mixed with dignity.

YELISAVETA SMITH: During the first month of the war, I was in the west of Ukraine with my son. When the Kyiv-Region was free of Russians, I

returned back and I went with the DoP to the just de-occupied city of Chernigiv, very close to the Russian border. For me

personally, that was a very traumatic experience. I saw what Russians had done in Yagidne village, where they put all the

inhabitants of the village in a school basement and a lot of them were killed for no reason. The city Chernigiv was severely

bombed, there was no food, no electricity, no water. We went to the graveyard and discovered those endless massive graves.

That was very traumatizing, to realize that all these dead are part of a family, neighbors. I was so shocked to see what the

Russians left behind, namely total death.

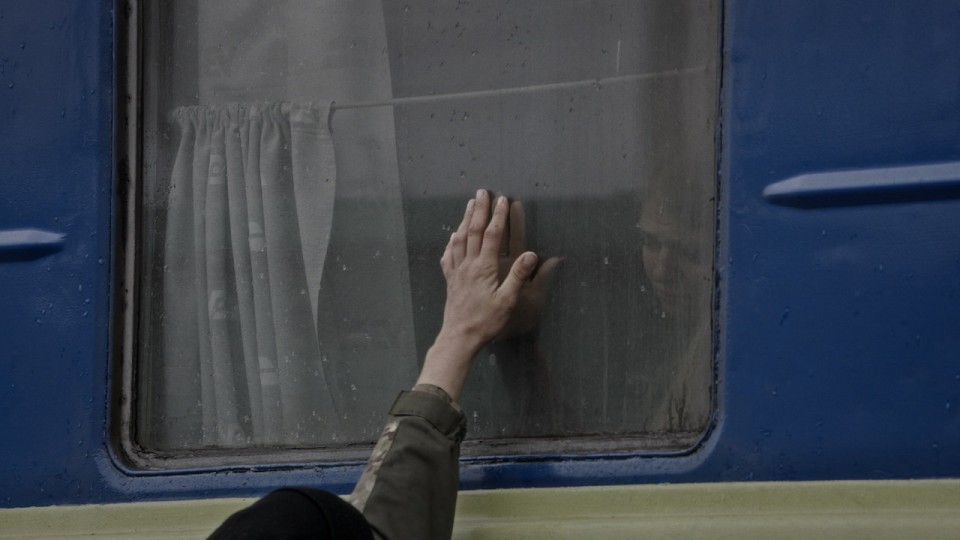

I’d like to get back to editing since I had the impression that there was, apart from the sky, a second leitmotiv – the trains

and rail tracks which span an arc from the first images to the last. They are telling something about separation, maybe also

about escape and a new beginning. Do you consider it as a main motif? What about its meaning?

YELISAVETA SMITH: I’m very glad that this is readable for the viewers. Due to the rocket attacks, we don’t have airplanes any more to travel.

Train has gained a lot of importance. We move by train or by car. The evacuations at the beginning of the war were predominantly

train evacuations, since they have huge capacities. Then we noticed that trains are connecting cities at the frontline with

cities far from it, mostly they are connecting families and soldiers who are paying visits to each other. We definitely built

the film’s arc around the railway scenes.

How long did you work on the editing?

ALINA GORLOVA: I’d like to highlight that I was only partly involved in the editing process. Yelisaveta and Simon did most of the editing.

We didn’t work with an external editor, but we did have some editing consultancy. Our editing consultant was the Austrian

film editor Dieter Pichler. When it came to working on the sound level, there was also a connection to Austria. We spent ten

days in Vienna, where we had a very inspiring artistic encounter with the composer and sound designer Peter Kutin.

YELISAVETA SMITH: It took us ten months and very often it felt like electricity going through your body. I was very happy about the result

and so relieved once it was finished. It was a very intense time. Editing meant days and days in a dark room, I love the metaphor

Simon has found for our editing process.

Can you talk about

it ...

SiMON MOZGOVYI: Sure. You remember the scene with the artillery unityoung guys are crystallizing their shooting skills. One of them is shooting;

when he’s out of bullets, he says, “I’m empty.” And the next person replies, “I’m covering you.” That’s how we worked in the

editing room. We were switching: When one of us couldn’t stand any more making the cuts, the other person would take over.

For the two of us, there was no need to be present permanently in the editing room. One could go filming while the other continued

editing. We filmed a lot in the southern and eastern parts of Ukraine in spring 2024, with no weekends, switching between

shooting expeditions and the editing processes. I think we deserve to be decorated with some stars on our shoulders.

ALINA GORLOVA: Simon and Yelisaveta accomplished an amazing work in terms of dramaturgy. We analyzed the whole footage together, but to create

a structure out of these very observational scenes and put the scenes in the right place in order to create episodes, that’s

really a great job.

YELISAVETA SMITH: I can tell you a story. We had two blackouts during important phases of the editing process. The first was at the time we

had to finish the rough cut. We found a place in Odesa connected to the port and therefore had electricity. We took all our

equipment, went to Odesa in order to continue our work. We were at the seaside, spotted dolphins and falling stars and kind

of discovered the positive side of the situation. When it came to the fine cut we re-lived exactly the same situation, we

left Kyiv and went to the Scientist Eco-Station outside the city to be able to concentrate on the work and then

blackout

again. Luckily, they had solar batteries. Our producers started joking that apparently, we had a sense for predicting blackouts.

I’d like to get back to the collective aspect of this project, with regards to both, the production and the creative process.

What’s the very important point about this spirit of collectivity and being strong together? Is it the only way of working?

YELISAVETA SMITH: I wouldn’t say it’s the only way. All of us are able to work separately, but

under circumstances of war, the horizontal

connections really mean a lot. And I think these horizontal connections are what, on a broader level, make us, Ukrainians,

survive. Going through this together with your friends, with people who think the same as you, gives you a shoulder by your

side. Sitting on your own in a dark editing room with this terrible footage, is very hard. Having people around you who are

close to you, really helps a lot.

ALINA GORLOVA: I agree. Of course, we can work independently. I can speak for myself, I wouldn’t make such a film alone. None of us. To

cover and handle so many places alone, would be impossible and wouldn’t be such an interesting process.

SIMON MOZGOVYI: I can’t see the purpose of doing this alone. A film like MILITANTROPOS is not about career achievement. It’s our response

to what is happening to us, about how we relate to our country, to our families, to our roots. We are connected to the place

where we were raised. Under these kinds of circumstances, we are not thinking about the industry loss. We are trying to achieve

the creativity of documentary filmmaking, to keep it strict, to look deeper. It’s not about making a chronicle, about producing

footage just to testify, but it’s about making something bigger. That was our goal, and it helps us be able to connect to

you.

And if I understood you correctly ... There’s more to come.

SIMON MOZGOVYI: MILITANTROPOS is the first part of a trilogy.

YELISAVETA SMITH: We already work on the second one.

Do you all have the impression of having become a militantropos in your way of being?

YELISAVETA SMITH: Definitely. We are very transformed.

SIMON MOZGOVYI: Yes. Absolutely. I see it positively, since it gives us a new meaning of existence. Democracy and freedom are not granted.

It has its cost, and societies have to fight for it. All together, we have to give something to be a human being.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

April 2025