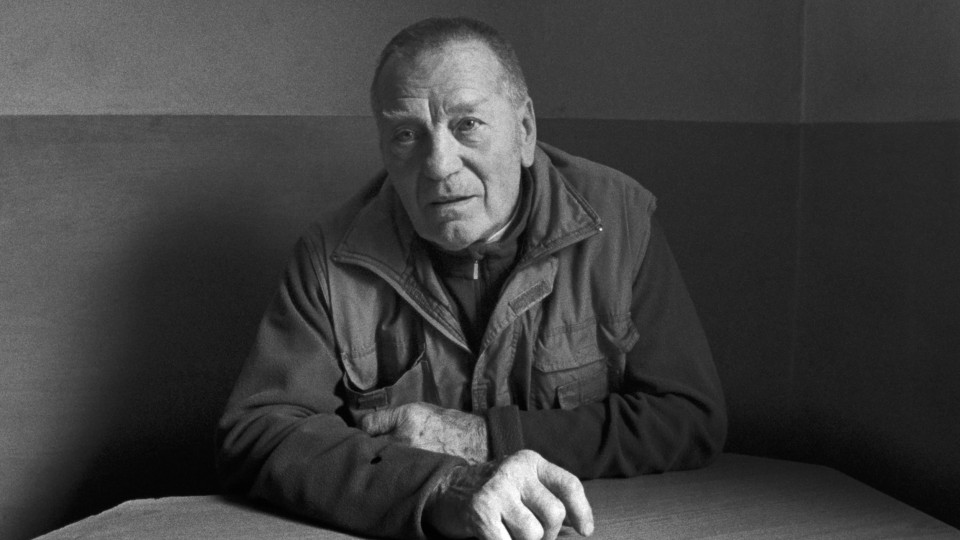

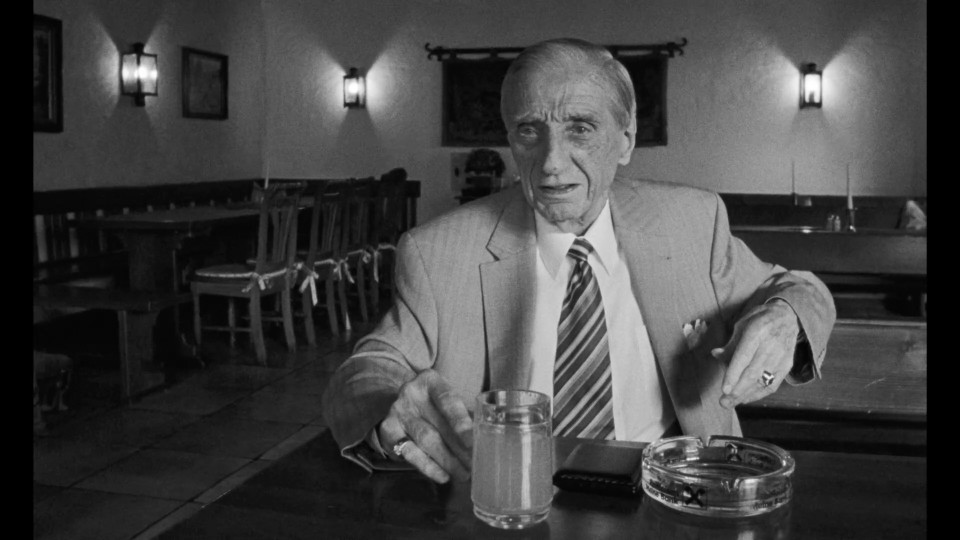

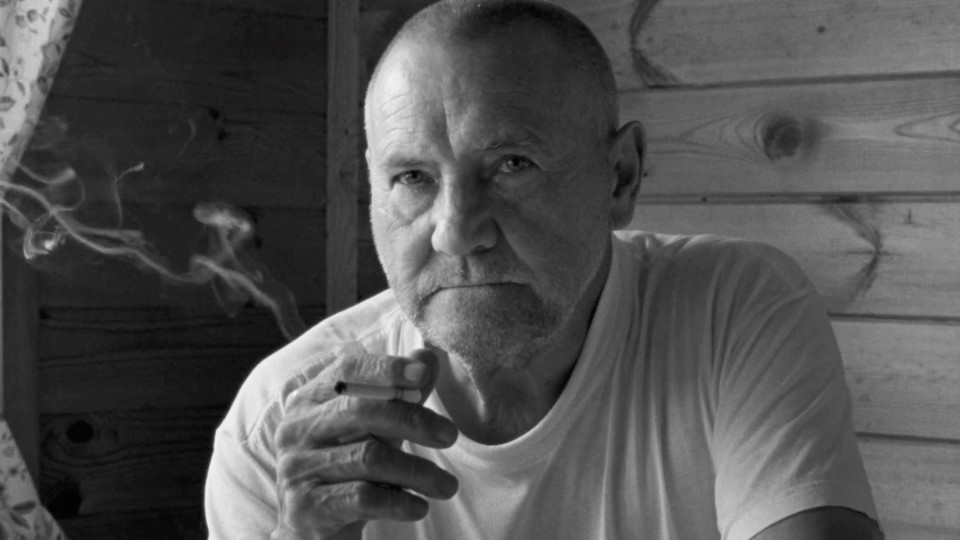

If Tizza Covi and Rainer Frimmel don't travel for their film project, they plunge beneath the surface of their city. A fascination with the underlying melancholic aspects of Vienna songs leads them to one of its most outstanding interpreters. Kurt Girk’s intriguing account of his life is interwoven in Notes from the Underworld with the city's gangster milieu of the late 1960s in the shape of its legendary protagonist Alois Schmutzer; the two men are bound by a lifelong friendship as well as a serious, harrowing travesty of justice. Tizza Covi and Rainer Frimmel present black & white portraits of two men, full of contrasts and the contours of a fading time which these protagonists have experienced in a rich range of color.

Your previous films together are all associated with one or more journeys. In Notes from the Underworld you have stayed in Vienna. Has the legendary Café Schmid Hansl, which is after all very close to your home, been a source

of inspiration for a long time?

TIZZA COVI: We have been fascinated by the songs of Vienna for a very long time. There have always been a large number of cafés and bars, right across Vienna, featuring a wide variety of singers and some really old Vienna songs. As always, our interest is very strongly influenced by the people and the stories around them, but also by the places where these songs are performed.

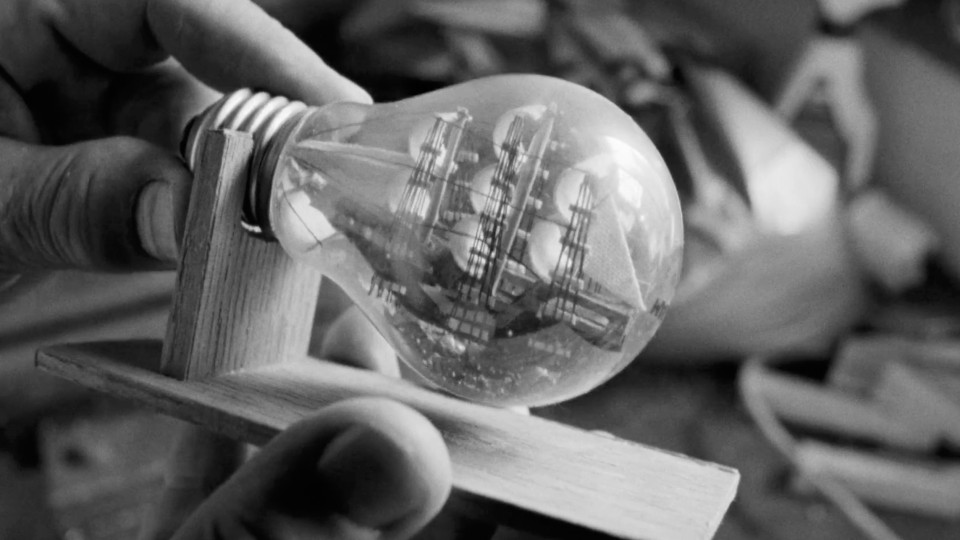

RAINER FRIMMEL: The typical songs of Vienna have two aspects. On the one hand, there is the folk element, but at the same time they can have considerable depth. I hope people who see our film will come to appreciate that these songs are more multi-faceted – just like the people who interpret them. We came across Kurt Girk at concerts we attended many years ago.

Was it also your intention here to work in a more documentary style, as with your first project together, That’s All?

TIZZA COVI: Actually, the decisive factor in the choice of the documentary form was the impossibility of working with these personalities in a fictional context. We wanted to capture the stories they told and share those stories with the audience. Far too much would have been lost if we had adopted a fictional format. So we decided to use a very strict documentary approach.

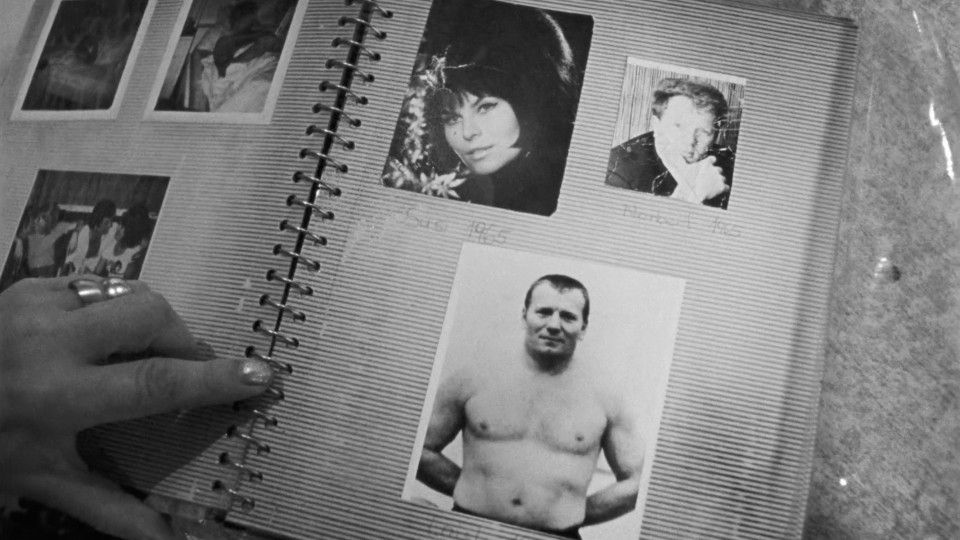

RAINER FRIMMEL: We filmed in 2017 in 2018, initially with Kurt, but unfortunately while we were filming he became very sick. Then we worked with Alois and the other protagonists. Of course the time factor was also part of our motivation, especially with regard to capturing Kurt and his stories, in the face of a disappearing world.

There are two outstanding performers at the center of Notes from the Underworld : one is Kurt, the singer, and the other is Alois, who made a name for himself on the right and the wrong side of the law with his irrepressible energy. How did the two of them come together for the film?

TIZZA COVI: Rainer has always been very interested in the Vienna underworld, and in particular in the card game Stoss. And we accompanied Kurt Girk to his concerts over many years. We only discovered after some considerable time that Kurt was one of Alois Schmutzer's closest friends.

RAINER FRIMMEL: Alois Schmutzer, our other leading protagonist, is considered a legend in the so-called Vienna underworld. He was one of the main figures in Stoss gambling in the late 1960s. The fact that Kurt also moved in those circles was always kept quiet in his biography – as was the period he spent in jail. He never talked about it much, and that made us curious. And that's how the connection with Stoss gambling and with Alois came about. The story of the criminal case which features in the film emerged as a result of that.

The memories are initially in a more linear format, but gradually this turns into a mosaic: new interviewees appear, and some memories are re-examining. At what point did you perform the research – which must have been more like an investigation? What form did that take? Did it perhaps get out of hand?

TIZZA COVI: It really did get out of hand, in the sense that we tracked down an incredible number of very interesting protagonists, including other Stoss players: prison guards, police officers, etc. When we first viewed the material we were able to reduce it to 5 hours. In the long and very tense editing process afterwards, we found we were losing more and more of Kurt and Alois. Which meant we had to make a decision: were we going to produce a portrait of the customs and morals in that period from all perspectives, an anthology of the Vienna underworld, or should we focus on our initial aim, which was the story of Kurt and Alois and their unjust convictions for the postal robbery? We decided on the latter.

One of the contemporary witnesses describes how, after the gunfight, Alois takes his attacker to hospital in his own car. That seems to exemplify the paradox of this vanished world, which was marked by the interplay between humanity and brutality, revolt against the power of the state and fairness according to the rules of the gangster world. It brings to life a period when the authority of the lawmakers came up against an authority based on physical power and superiority. How did you respond to this ambivalence?

TIZZA COVI: The ambivalence is what constitutes our interest in a person. It's what reflects the humanity.

RAINER FRIMMEL: We really didn't want to romanticize or mystify this milieu. We don't pass judgement; we let people speak. Obviously, in a context like this the question of truthfulness always arises. That's always a problem when people are describing their memories. Every form of remembered story raises the question of truth. Veracity is a central issue, but we are also concerned with stories, because we are dealing with storytellers. And Kurt is a particularly gifted one.

TIZZA COVI: The indignation about their unjust convictions, which slumbers within Kurt and Alois, is something we wanted to convey too. You still find books that claim Alois committed the robbery, even though it’s been proven that he was not involved in the crime. No matter whether he was a Stoss player or not, whether he got into fights, a great injustice was perpetrated there. He was sentenced to 10 years behind bars because it was claimed that he instigated the robbery.

The more the film progresses, the stronger its political dimension becomes. Misuse of power by the police and the judicial authorities becomes apparent, cruel methods of incarceration emerge, and this also echoes the terrors of the Nazi regime and the role of authority and the state in the first postwar decades.

RAINER FRIMMEL: The film is also concerned with the postwar judicial system and the conditions in prisons at that time. We've excluded accounts of these conditions in the direct narratives of the protagonists, Kurt and Alois. Their stories on that subject could be a separate film. We wanted to convey the conditions in prisons more from the perspective of the prison guards; I also consider them to be victims, in a sense. We're dealing with a time when prison conditions were really terrible and young guys without any training were brought in to work as prison guards. It wasn't just that conditions in penal institutions were catastrophic: the reasons why people ended up behind bars were horrifying. You have to remember that homosexuality, for example, was still a criminal offence, and many homosexuals were kept in prison in terrible conditions. One aim of the film is to point out that everybody – whether they are guilty or not – has the right to be treated humanely.

Notes from the Underworld is also a story about resilience. Despite their terrible experiences, these two men have found contentment in life.

RAINER FRIMMEL: They both experienced the Nazi period, the air raids at the end of the war and the subsequent Allied occupation. They grew up being confronted as children with open, state-authorized violence on the street. Both of them spent many years in prison, but due to their strong personalities they didn't let that break them. Today they both convey the very strong impression that they regard every day of freedom as a gift.

TIZZA COVI: That's why we focused first on the subject of their childhood, so that what comes afterwards is easier to understand; we wanted to create an awareness of the brutality and violence that these men grew up with as children.

The main section of the film is in black & white. Together with the very long shots, that creates a very photographic feeling. The length of the shots also conveys something of the long lives the two men have had, and the changes they've experienced: it creates a frame where a face alone, and facial reactions, can convey so much.

TIZZA COVI: We regard these unique faces as extremely fascinating, and in combination with the course-grained film they develop considerable power. In order to portray more about the protagonists and their lives, we filmed them in places where they enjoy spending time and feel at home.

RAINER FRIMMEL: We aimed for a natural image. The way it is when you sit facing someone and talk to him. We filmed on Super 16 mm film again. One roll of film lasts 11 minutes, and we know that within that period something essential had to happen.

The film has a kind of epilogue in color, where the two protagonists – after having told everything indoors – go outside, moving around in a present-day context. What prompted you to instigate this transition?

TIZZA COVI: Our concept was to use interiors exclusively until we got to the subject of freedom. The idea of switching to color for the exterior shots didn't come about until we were editing, because then in any case we had to weigh up where and how we would place the exterior footage, although basically the subject of freedom was always meant to be at the end.

RAINER FRIMMEL: For Alois, living in the countryside – the way he does now – is the essence of freedom, because he can finally live in a way that was denied to him for so many years. For Kurt freedom means going to the inn and singing there. That's his life.

The Vienna songs themselves, are also central features of the film. Why did you decide to play them in their entirety?

TIZZA COVI: The song we placed at the beginning is a way of indicating that this film will feature long shots. It's a formal introduction for the audience to the tempo of the film. The thing I feel extremely sorry about is that Kurt Girk can’t experience the premiere. That would have been his big moment. A massive audience, applause and him up on the screen, a huge figure. The choice of those two songs originated with Kurt: they were his favorites. The final song, Today the Old Times Were With Me, but Sadly Only in a Dream, is particularly important to us. It was Kurt and Alois's absolute favorite song, and every time they got together and we were around, they sang it. It was their song.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

December 2019