At first, Juri Rechinsky only went as far as the Ukrainian border, supporting friends, family and refugees in the first weeks

of the war. But as he came to appreciate the almost inconceivable repercussions of the invasion on Ukrainian society, his

need to risk a trip to the front became more urgent. DEAR BEAUTIFUL BELOVED documents the filmmaker's journeys to his own borders and into the invisible zones of the war region, along the grim routes

of grief that has become an everyday phenomenon.

A talk with director Juri Rechinsky and editor Andrea Wagner.

You’ve been living in Austria for many years. How did you personally experience the beginning of the war in February 2022?

What does this state of war mean to you and your connection to Ukraine?

JURI RECHINSKY: February 24, 2022 was absolutely catastrophic. First thing in the morning – news about the war, news from my family living

close to Kiev. They woke up to heavy explosions and a sky of surreal red color. For me, as for many others, this was a very

sharp cut, a radical change within ourselves, in the world and the circumstances we live in. It’s still hard to accept. After

two and a half years you get used to it, but it still makes no sense.

How did the idea of making a film come about?

JURI RECHINSKY: Shortly after the outbreak of the war, I didn’t feel the desire to do anything related to film. It became quite clear, that

whatever we did as filmmakers was failing to prevent us from war. I was much more focused on concrete and physical action:

Go to the border in Hungary, meet someone’s relatives. Go to the next border in Romania, meet my sister, meet my friend’s

wife with a small child, bring her to Vienna, figure out how and where they should live. On the first day of war, I joined

a demonstration and realized that all this chanting and singing was a job that could be done by someone else. What should

I do? What else could I do? On the border of Ukraine with Romania I saw the huge flow of people, their emotional state, the

things they were taking with them. This was a direct reflection of war. It gave me an understanding of the scale of something

you’re not ready to face. Then I had a long discussion with my sister about our options – what to do, how to help, how to

react. It was actually her who suggested I should use my background of a filmmaker, at least as a starting point. First, I

thought about a journalistic approach, since it would be more immediate. At some point I got a call from my production company,

they’ve said they were worried about me and that if I would like to document something related to the ongoing war, they would

be ready to pre-finance it. I had been working with them on a fiction project, we had a long and complicated financing process

which we closed on February 17, 2022. The whole concept was crushed by the circumstances only a week later. I took up their

offer. In April, we returned to the Hungarian border with a small film crew including my sister and spent four or five nights

shooting. Back in Vienna, I edited the material, and the result gave me the impression of being at the right place doing the

right thing.

How did you develop the main lines you wanted to focus on? Basically, I imagine, what war means beyond the military operation?

JURI RECHINSKY: In May 2022 we started the application process and figuring out the concept. I started research and drove to every checkpoint

along the Ukrainian border with Poland, Slovakia and Hungary. Based on my observations of volunteers and refugees, I wrote

the concept together with Kseniya Kharchenko, who had come to Vienna as a refugee. I needed help given the time pressure and

the intensity of the experiences we had during research. She is an excellent writer and was directly affected by the whole

situation.

How did you come to choose Andrea Wagner as the editor of DEAR BEAUTIFUL BELOVED?

JURI RECHINSKY: Andrea is the editor of my favourite film, Megacities by Michael Glawogger. I rewatch this film before every project’s first

shooting day. It’s a huge source of inspiration.

Andrea, what appealed you about this project?

ANDREA WAGNER: I saw a rough cut of the Hungarian part, which was only a layout of material. Of course, it felt like a fascinating project,

about real life and a very challenging topic. The crucial point was to find out about the topics Juri would be shooting. The

themes were not absolutely clear from the very beginning, he came back with different options from his research. The material

Juri brought from Ukraine was totally different to that from the Hungarian border, which comprised images we were familiar

with from 2015. Still, I was moved by the pictures with the babies and the kids on the train, but what really impressed me

deeply was the first material he brought from Ukraine.

It seems you encountered a lot of voluntary humanitarian initiatives. Who did you want to work with?

JURI RECHINSKY: Once the concept was written and applications done, I realized that I had been fighting with the desire to go to Ukraine since

February, and it was only getting stronger. For some reason I was certain that if I avoided this trip, I would have regretted

it until the end of my days. I managed to convince the production company, we tried different options to secure my passage

out of the country and failed. But I was in such a state that we just packed everything up – without any guarantee that I’d

be able to get out of the country again. That was the point when the movie really started. I had a crew of people in Ukraine

who I’ve been working with since many years, starting from sickfuckpeople and Ugly. When we entered Ukraine our research was

still mainly focused on refugees; I wanted to find out about their story before they crossed the Ukrainian border. We proceeded

step by step closer to the homes they were leaving, gradually increasing the level of risk.

Where in Ukraine did you start shooting?

JURI RECHINSKY: We shot in the Donetsk region, between Bakhmut, Slowjansk, Kostjantyniwka. The shooting was preceded by weeks of research.

First, I came to Kiev, then my crew sent me to Dnipro, much closer to the front line. From there I started to follow volunteers

evacuating people from their homes in Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia. I think the first trip was to Nikopol, a small city right

in front of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, which was heavily bombed every day. On clear days you could see Russian

soldiers on the other side of the river, and of course the enormous structure of the nuclear plant. It was a time when everybody

was worried and nervous about whether it would explode or not.

How did you deal with this state of fear?

JURI RECHINSKY: By taking smaller steps than you would usually. It’s not about planning a regular shooting day. You could come back home

without your legs, not return at all or end up in captivity – get in real trouble that might end your life or change it forever.

Our approach was to talk to people who were physically present in the exact area we wanted to visit when we were hesitant

about doing so because it was dangerous. These were fixers, journalists, volunteers, Red Cross drivers, paramedics, soldiers

– anybody who had to travel to such places recently. In the best case – on that very day. Things can change so quickly in

war, information from somebody who worked there a week before might have been very outdated. So we were collecting such statements

and then in the evening deciding if we want to go there tomorrow or not. I experienced work in the war zone for the first

time in my life; you learn every day to make more precise predictions, but in the end it still remains an intuitive decision.

Sometimes this intuitive decision is so strong that it goes against reason. Every new step was an increasingly dangerous one,

until the one you realize that it was one too much. This last step I made with Elisabeth and Jonny. I went with them to Bakhmut

on first of September 2022. Half a year later Bakhmut has become an iconic city and was completely destroyed. It’s only ashes

and skeletons of buildings. In August/September 22 nobody wanted to go there, something strange was beginning to happen, but

it wasn’t quite clear what it was. Elizabeth and Jonny went there almost every day, aware that it was getting more and more

dangerous. They were maybe the last guys to go there to evacuate people.

How did you come to focus on your two main strands – the evacuation of the elderly people and the transport of the fallen

soldiers?

JURI RECHINSKY: We were doing research in a shelter for refugees called Ocean of Kindness, and I realized that this forced movement for these

old people was the scariest thing. Nothing was within their control, they didn’t know whether they would survive the trip,

they had no idea where they’re going to. They were missing their homes, routines, neighbours, favourite teacups, jars of honey.

I saw in this group of old people every possible human reaction to a major change in one’s life. I was devastated by what

I had seen, and I can’t explain this effect. Maybe it was the fact that those people had to go through this experience again

and again.

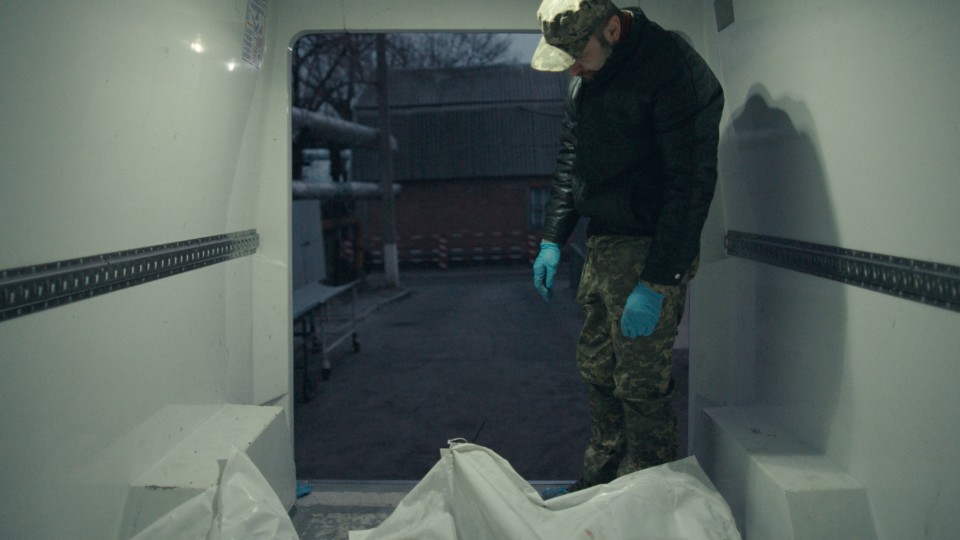

As for the fallen soldiers, there were many points: One of them was that I drove myself a car with the dead bodies at night

on a very strange road. I was allowed to do so because the driver was too tired and had started to fall asleep. I was driving,

and I felt a very different kind of responsibility behind my back. I never drove that safely before. A crash would have been

unforgivable. In the morning, when we arrived at the morgue, I witnessed how the bodies were handled. Morgue workers were

busy with their routine, everything very practical, professional. Standing there exhausted after many hours of driving, watching

the face of a dead guy I sensed a feeling of overwhelming beauty. For one family at least, this object, this heavy, stinking

object, is the most important thing. Without getting to see it, getting to touch it, they would not be able to go on living.

I wanted to talk about this transformation. If you keep reading news for months, victims become numbers. What happened to

me in this morgue was, that each of those numbers became someone’s beloved person.

Did you start editing at an early stage, once the shooting of the evacuations was done?

ANDREA WAGNER: After shooting the evacuations and the elderly people in autumn, it took quite a while to get the material subtitled. It was

late winter then, Juri was back in Ukraine again, shooting the corpses story, when I started to work on the autumn material.

Which means first viewing and sorting out, making first montages, creating first rough, very rough chapters of the evacuations

and the old. Then Juri came back with the material of the body-bag story. At that time, we were not aware that he would not

leave Austria again.

The original idea, as I now recall, was to track people who had been bombed out, fled to the West, lived there for a while,

but then returned home – of course, at that time we all thought the war would soon be over. We wanted to accompany them on

their journey up to the moment they stepped back inside their homes. But that is exactly what never happened. We already had

a huge amount of material, so we said to ourselves: "Let's work with what we have". And at some point, it turned out that

we had everything we needed. It features theatres of war in the background, which was enough.

The persons you film are constantly on the move, be it in vans, in cars, in trains, they’re getting evacuated, transferred,

relocated, or they’re leaving their homes. Does this ongoing movement also tell something about being uprooted, about the

loss of certainties caused by the war.

JURI RECHINSKY: My question was: What is war? I was witnessing it from the media and from this side of the border while I was in Austria,

but I went to Ukraine in order to have a direct experience of it. In the media, war is one thing. In many different realities

it’s something different. It’s a thing which forces movement. You cannot shoot a film about war without movement because everything

is moving. It’s like an ant hill during a storm. At the same time, some of the elderly people we were evacuating and following

hadn’t left their flats for years. That was for me a scarier and more brutal thing than their condition right then. They were

similar to my characters in sickfuckpeople – those invisible people, part of society but unnoticed.

I’m aware that I’m jumping between different fragments of different stories, but you have to excuse me. I try not to talk

about it very much, the memories put me in a certain state. I remember too much. It was such an intense experience, and there’s

so much stuff I haven’t integrated yet.

Andrea, can you tell us what the major challenges were for you?

ANDREA WAGNER: It was real work for me after a long time. A great privilege to be able to look at it without having to be a part of it.

When I saw footage of dead soldiers in the morgue for the first time, I got scared. Just three seconds of a difficult take

forced me to stop working. My first thought was: how on earth can I continue working on this film? And can I do this film

at all? I know cinematographers who frame a shot quickly and then close their eyes at the moment they shoot, if things are

happening in front of the camera that they don't want to take in. But that doesn't work in the editing room. I have to look

at it. It took me a week, then I started to face the pictures. When Juri came back, we cleared some footage together and made

a selection that was OK for me.

I have to admit – and it's hard to say this – you get used to certain images. Over the course of several months of work, you

lose all the emotions you had the first time. I saw only black and white sacks and wasn’t affected by the contents anymore.

That was one of the biggest challenges in editing this film. So in the beginning I worked on my own, preparing sequences to

watch together. During the second half of the editing process, we mostly worked together. Juri’s gaze was also very important

to me because he owns the language and therefore perceives certain sequences when it comes to words in all the nuances. I

also had Ukrainian assistants inside the country, and as well as communicating with them about the film I’d hear stories,

too. Often I’d be impatient, because the subtitles I wanted hadn’t arrived in time – until I realized there simply wasn’t

any electricity because there’d been another attack on Kiev. It was a very particular situation in the editing room, experiencing

this different reality for the assistants who got in touch each day from a world at war, hearing about their losses and feeling

their fear. At that moment it would always put into perspective a lot of what was happening here in our country.

There’s a very striking sequence at the end with people kneeling at the roadside when the convoy transporting the dead soldiers

is passing by. Can you tell us more about this scene?

JURI RECHINSKY: Andrea and I had a lot of discussions about the images of the people kneeling at the roadside.

ANDREA WAGNER: When I saw these images for the first time, I was so stunned. I’d never seen anything like that before. Juri had a different

view. For me it was a wonderful image to show how society participates and reacts.

JURI RECHINSKY: That was the reason I understood and accepted it. It is really a show of respect, and that’s touching, even though I don’t

like the formal and the ceremonial aspect. The car passes by, the people kneeling on the street get up again, and life goes

on. The mother of the soldier will never recover. This show of respect cannot be the payment for the loss of a son. You cannot

give anything to the mother of this child that might excuse his death.

How did you finally manage to go back and forth between Ukraine and Austria?

JURI RECHINSKY: I went there twice. How did I manage to cross the border back to Austria? With powerful support from various institutions.

A lot of people wanted to help me; I’m still surprised. I came back through official channels, but not without difficulties.

The worst experience for me in this whole period of work was when I’d finished shooting in Ukraine and had to wait for permission

to leave the country.

What was your core motivation to go there, despite the risk you had to take?

JURI RECHINSKY: I wanted to take part in the war with tools I’m familiar with. I cannot ignore that a war is going on. Compared to this huge

situation I’m a piece of dust, but still this piece of dust wants to do something and cannot just live its life as if nothing

is happening. It wasn’t fun to watch corpses every day for nine months. When I left for Ukraine in 2022, I had no idea what

I would find there. How you feel yourself when you’re walking through a minefield, or carrying someone's grandmother from

a fifth floor during shelling, or searching for a dead friend in a refrigerator full of body bags. I had this experience and

I’m not sure whether I would repeat it to myself. I felt an urge to do it. Now I have some knowledge of the situation, I’m

wondering if I should go there again. I have to question myself about that feeling; actually it would be against any reason,

but there is still some attraction.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

June 2024