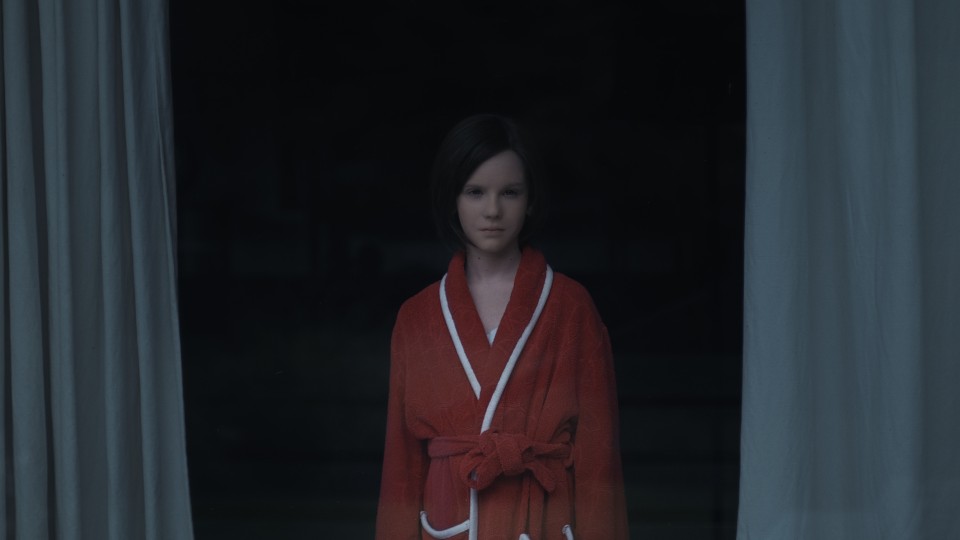

A beautiful house. Countryside all around. A father lives alone here with his 10-year-old daughter. That's what it looks like at first sight. The girl, who swims, speaks and laughs, is an android machine programmed to keep alive the presence of a girl who was lost – while also satisfying the desires of its owner and relieving his loneliness. At some point she vanishes but continues to function in her own way. Sandra Wollner’s THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN does not move along narrative lines but penetrates uncomfortable mental spaces, raising difficult questions in the zones of encounter between artificial intelligence and human perception.

The title of the film, THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN immediately throws up a certain line of questioning. What kind of squabble with our existence is at the root of this, your second feature film – perhaps of your film-making in general?

SANDRA WOLLNER: Squabble is good. That alleviates the tragedy a little. We live in a world which appears relatively structured and organized in terms of meanings, but at the same time I feel it's possible to sense the chaos behind that. In a way, you can sense how fragile this reality is. Maybe I can illustrate that with an example. If I repeat the word "Marille" 500 times, it loses all meaning. There is a brief moment when you lose your bearings, and everything collapses into pre-linguistic chaos. The people in the film are marked by this feeling. The vague suspicion that this world, in essence, is anything but organized, and perhaps only appears to be so in our perception.

Gradually android robots are starting to play a role in human existence, even when a robot like that in THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN is still a dream of the future. Was the android robot in itself the central topos that provided you with an impetus to start writing?

SANDRA WOLLNER: The idea of making a film about a childlike android came originally from Roderick Warich, with whom I wrote the screenplay. I was initially working on a different story, where a girl increasingly has the feeling she doesn’t see the world the way it really is. She develops the desire to move away from her own viewpoint, a human viewpoint. The desire to see the world the way it is, without evaluating it, and instead simply just to be. Essentially, like an object. When I look back now on the process that gave rise to THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN, I realize that's why the idea appealed to me so much: because the robot girl represents the vessel I had been looking for previously.

To what extent were you also interested in debating the isolation of the individual in this film?

SANDRA WOLLNER: I was interested in the virtuality of individual reality, i.e. the structures that organize reality. To what extent are we always merely conversing with the persona of another person? To what extent can we really step out of ourselves and actually see the world as it is? Or is it just the appearance of this world? That's the crucial question driving me: how virtual is our own reality? The people in this film very much want a genuine opposite number, but really they're just looking into a mirror. Consequently every conversation with this robot remains a monologue at first, which forces them back on their own isolation, their own virtuality. After all, our human experience is characterized by a self, an awareness, which is what actually makes us thinking beings in the first place. It is by means of this self that we separate ourselves, consciously to some extent, from the world. So essentially we are always fighting this isolation.

Even in your first film, The Impossible Picture, loss and decay, disappearance and memory – as well as the desire to hold on – played a crucial role. Do you regard THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN as a fictional narrative or more as an essay about loss, memory, desire and longing? Would it be accurate to locate your work in films at this interface?

SANDRA WOLLNER: I have the feeling that the kind of cinema which interests me at the moment is located at this interface between narrative patterns and subjective moments of observation. It seems to me that the majority of contemporary art, apart from film and literature, doesn't subjugate itself to these narrative conventions – and perhaps even deliberately rejects them. That is also decisive in my work. I notice in my own artistic environment a powerful desire to unify these phenomena. To make a kind of metaphysical film which, however, also tells a story. The need for narrative and the radical, subjective observation of an issue are of equal value here.

Is the image, or the medium of film itself, more like a means for you to make contact with this pre-linguistic level?

SANDRA WOLLNER: That’s an aspect of the cinema which interests me, yes. The return to pre-consciousness: cinema as dream. A cinema where voids are also possible, along with dark echoes and narrations that dissolve – just like a dream, in fact. In this case, a very curious one.

To what extent are you also concerned with applying a vision of the future to the present?

SANDRA WOLLNER: It was important to me from the very start that the film should not be located in a sci-fi setting, because the issues addressed by the film have essentially been anchored in our everyday present for a long time. I think the term fairytale is quite appropriate for this film. Kubrick’s idea for A.I., for example, essentially refers back to Pinocchio, and the film tells the story of becoming human. Actually, I wanted to do precisely the opposite, but nevertheless the themes and characters in the film are archetypical. The people there remain outer shells, to a certain extent, never becoming completely genuine. It's only by means of the androids, which serve as receptacles for their memories and concepts, that they attain clear delineation. And the robot itself is, in the final analysis, more my idea of robot than an illustration of a technical reality.

In the middle of the film a turning point arises which causes us to lose sight of the first two protagonists. Are you also interested here in pursuing the motif of loss on a formal level?

SANDRA WOLLNER: Definitely. I wanted to show a very human android which at first only reveals in isolated moments that it’s actually a machine. So when we are observing this being, we can't avoid humanizing it. It's only with the loss of the characters and the derailment of the narration that I was able to indicate a non-human perspective. As viewers of the film we have a wish to see the narrative ended; we want to know what happens next. But since it's only the way this robot girl has been programmed, what happens next is completely irrelevant. She doesn't attach any meaning whatsoever to the content or to her own fate. One program is deleted, and something else continues instead. I found that fascinating in formal terms.

A disturbing feature of the first half of THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN s the ambiguity of the father figure, where the sense of grief and loss about the disappearance of his daughter and sexual desire for her (or another underage girl) achieve an interlocking independence. Another possible view is that he is able to program in one single robot memories of his daughter and his sexual desires which were triggered by her. The ambivalence remains. Why do you play with these aspects?

SANDRA WOLLNER: First of all, it's in principle just like Vertigo: a man attempts to bring the object of his desire back to reality – which is in itself of course a problematic topos. In my film a man has already brought the object of his desire back to reality and can shape it entirely according to his own wishes. On the one hand this desire is reasonable, because it's dictated by loss and grief concerning a real person, while on the other hand it is unreasonable – far more dynamic than desire alone, because he wants to live out his sexual fantasies. I found it interesting that both exist at the same time and can also be lived out simultaneously in this virtual being. The bizarre aspect is that it doesn't make any difference at all to this being: it even says it’s pleased, because that's what it's been programmed for. It's unbearable for us, but it's a matter of complete indifference to the robot. Personally, I find the idea incomprehensible, offensive. But it doesn't matter at all to that object. And of course that is a provocation for us. A challenge which essentially throws us back on our human condition.

The idea of telling a story with an android robot entails a technical challenge for the production. What can you tell us about the genesis and implementation of this idea in technical terms?

SANDRA WOLLNER: For a very long time I worked on the assumption that Jana McKinnon, who I've worked with in the past, would play the robot girl. Jana is a fantastic actress, and the preliminary work and conversations with her were essential for this film. But at some point I simply realized that I had to work with a much younger girl for this material. Actually, that did occur to me right at the beginning, but I suppose I was just afraid of going through with it and creating that image. Could I do that? Was it permissible to do so? It took a while before I could answer that question in the affirmative. And then with Lena Watson we found our actress, and she simply slipped into the role of the android. It wasn't an easy task. And the whole thing was only possible because of the incredible support from her parents, with whom we had a number of honest and fundamental conversations; they were present during filming.

Does THE TROUBLE WITH BEING BORN and your film work as a whole, occupy a space between what slips away from us, impossible to hold onto, and what won't let go of us all through our lives, dictating those lives?

SANDRA WOLLNER: The way memories and ideas are superimposed on one another is a subject that accompanied me on my last film: memory as the

narrative that provides meaning and identity, without which we would sink into meaningless chaos. Memory as programming, narration

as the fundamental basis of human existence. Everything has a beginning and an end: the myth of self-fulfillment, which after

all is also dominant in the cinema. In opposition to that is the fundamental endlessness of a machine's existence, with its

narration that can't be immediately comprehended. I find that fascinating.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

January 2020

Translation: Charles Osborne