Tizza Covi & Rainer Frimmel's new film enters the force field between a lion tamer and a former Mr Universe. Mister Universo is a filmic journey guided by iron muscles and lucky charms.

We have encountered Tairo Caroli before, in La Pivellina (2009). At the time you expressed the desire to film a story with him. What was it that Tairo conveyed to you at the age

of 14 which made you want to make a film with him? How had he developed when you re-established contact with him?

TIZZA COVI: Even then it was apparent that Tairo had the talent to do the wrong thing at the right time. That has a great deal of comic

potential but also embodies sadness and secures him a particular kind of sympathy. He unites within himself a number of facets

that make him a very ambivalent character.

RAINER FRIMMEL: We haven't lost track of Tairo since filming La Pivellina, and we talked to him frequently about working on a new film project together. In a sense he had been expecting it. So it

wasn't that we saw him again after a long break.

In La Pivellina it's a child alone in a playground, in The Shine of Day an unknown uncle who suddenly bursts into the life of a busy actor. Now it's a talisman that is mislaid. How do you

find the impulses which trigger the filmic journeys?

TIZZA COVI: Our stories always come across as very simple, but there is a great deal of mental work behind them. In retrospect it seems

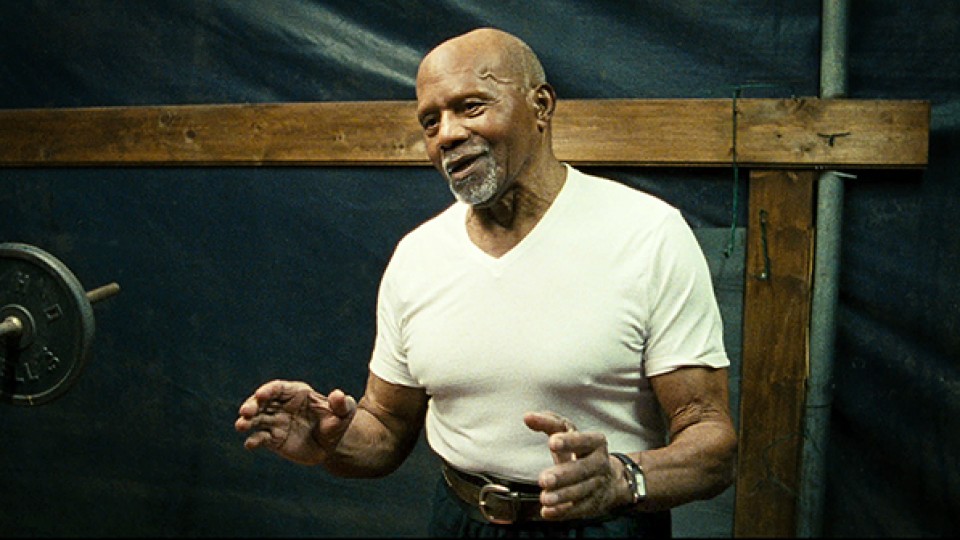

quite logical that we have written this story for Tairo and Arthur Robin. Arthur Robin is a former Mr Universe we met 18 years

ago, and we have wanted to work with him for a very long time. In the early days he had lots of film offers, but he turned

them all down because he had commitments in the circus. Working on a film like ours also meant leaving his protected space.

So he thought about it for a long time before deciding he wanted to try it, at the age of 88.

RAINER FRIMMEL: One of the challenges we always set ourselves is to link fundamentally different people in a story that is as simple as

possible. Different characters we want to feature in the film have to be brought into a relationship by plausible sequences

of events that really could take place.

An animal trainer and a bodybuilder – both require quite particular strengths – Tairo as an animal trainer, physical

as well as mental. The theme of strength, physical and mental, rational and irrational forces, appears to be central for you.

When did you become aware of that?

TIZZA COVI: I became aware of that during the writing process, when we explored the subject of superstition as an irrational force more

and more. Wendy Weber, our female protagonist, plays an important role, since she is herself very superstitious. Thanks to

Wendy, a lot of things became intertwined there.

RAINER FRIMMEL: The bending of the iron bar enabled us to represent in a very concrete manner the multi-faceted subject of strength in all

its forms. But a lot of things that seem to be absolutely key might well have simply come up during the work by the force

of chance.

What's the story about the curious place where it appears that the force of gravity is reversed?

TIZZA COVI: That place is to the south of Rome, not far from Castel Gandolfo, where the Pope has his summer residence. One element that

was particularly important to us in this film is counter movement, swimming against the stream, being different. The road

where everything rolls uphill instead of downhill provides a very fine illustration of this.

RAINER FRIMMEL: Many people claim that supernatural forces are at work here. It's a matter of subjective perceptions that could be explained

very simply, but then the magic would be lost.

Belief and superstition aren't only present in this environment; they also represent a subject that features in everyday Italian

life. A subject that has forced himself to the surface after making four films in Italy?

TIZZA COVI: Superstizione, a short film by Antonioni, had a lasting effect on us. The way superstition restricts the lives of many people and has a

defining influence on them is very apparent in Italy.

RAINER FRIMMEL: I think everybody is superstitious. Perhaps Italian people are more open about it. Superstitions are particularly prevalent

in circus life. The profession of circus artist is associated with many dangers, so there are a huge number of rituals that

are supposed to offer protection.

The title, Mister Universo, represents Arthur and the man who was celebrated in his youth as the strongest man in the world because of his muscle power.

Doesn't that also involve the question of who or what determines our fate?

TIZZA COVI: Arthur took his fate into its own hands even as a young man. He only had one aim in life, and that was to become Mr Universe.

And he succeeded by means of hard work. Today Arthur is a happy person. But it's easier to believe that his fate is determined

by other forces, such as a talisman.

RAINER FRIMMEL: And that's exactly what Tairo believes; he's got it into his head that Arthur will bend a new iron bar for him, a lucky

charm, and then he'll be able to get his life back on track. That's why he sets off in search of Arthur, without knowing whether

he'll find him or what will happen then. It was lovely to see that the encounter with "Mister Universo" really was significant

for Tairo. Not because Arthur taught him how to bend an iron bar or how to increase his strength, but because something happened

on a mental level. And Arthur in turn also benefited from this encounter. He's a very dignified person who lives very much

according to rituals; everything always has to be ordered. And suddenly Tairo bursts into his life and turns his world upside

down. It could have gone terribly wrong. But he liked him a lot.

This is the first time we have encountered Arthur in one of your films. How did you meet him?

TIZZA COVI: We met him in the late 1990s. At that time he was still working in the circus, and we went there to watch his show. He bent

an iron bar for us and gave it to us as a present. We still have it 18 years later; it means a great deal to us. We found

out about his life story and also met his wife, Lilly. The enthusiasm the two of them have for each other, and the way they

take charge of their lives, has always fascinated us. Today Arthur and Lilly live in a safari park. Lilly takes care of the

sound and picture filming of a daily circus show. Arthur checks the tickets, but he also does that with dignity and precision.

And I thought it was very beautiful that he emphasizes on camera what good fortune it was for him to have met Lilly. That's

what makes Arthur Robin the man he is.

Your narratives are always stories that are as close as possible to life as reality. The travelling professions of circus

people are by definition connected with movement, transience, volatility. By virtue of the fact that you have now depicted

this environment in four works, your narratives are also about the transience of life. As if the same starting point had gained

momentum, transformed your work into something different.

TIZZA COVI: Our work preserves many things that will not exist in the same form in future. It won't be long before there are no more

lion and tiger trainers – and in principle that's a good thing. They are professions that are dying out. Professions

that you can criticize a lot, but they have a great deal to do with human nature, not only for the people who do those jobs

but also for the people who want to see them. It's very important for us to preserve that without judging.

In the first images cages, bars and fences – the animals that have been robbed of their freedom – are very present.

A little later we see Tairo walking between the fences, and it makes you wonder whether he isn't a prisoner as well. Does

he represent a way of life where a high degree of freedom and a high degree of imprisonment are interconnected? Or is the

idea of freedom in the circus in any case a myth?

RAINER FRIMMEL: The early images of the cages are also intended to convey an overall feeling of confinement. We've been interested for a

very long time in the environment of the travelling circus. The idea of being in prison is something that has fascinated us

in each of our works. Wendy lives in a little cockleshell and performs contortions twice a day even though her doctor told

her a long time ago to stop for health reasons. It's possible that she won't even be able to come to the world premiere of

the film in Locarno because she has to put on her show every day. It's a cliché to imagine that the circus has much to do

with freedom.

In Babooska and also La Pivellina we mainly saw circus artistes training, and the action in the circus ring was excluded. Now in Mister Universo it's different. We see both Tairo and Wendy putting on their performances. Why is it important this time to show them appearing

in the circus ring as well?

TIZZA COVI: We definitely didn't want perfect footage of Tairo as a lion tamer. We limited ourselves to casual shots of the circus ring.

The act is intended to be part of the story without being blown up in the film to something spectacular. This view from behind

the scenes is a counterpoint to the excitement a circus offers from the perspective of the audience.

RAINER FRIMMEL: It was important for us to show the audience right from the start that Tairo is a real lion tamer who walks into the cages

with the animals and works with them without fear.We show Wendy putting on her performance because it fascinates us to see

how she can contort her body the way Arthur bends an iron bar. We wanted to close the film with that association.

Mister Universo is a road movie, partly cut as a parallel montage with Wendy/Tairo; there is the undercurrent of a love story and the theme

of searching – a theme that already emerged in La Pivellina and The Shine of Day, which this time ends with the search being successful. Do you regard it as the film where you most closely approach fictional

cinema?

TIZZA COVI: We wrote the screenplay for this film much more exactly and stuck much closer to the screenplay. People often ask us how

much our characters improvise. It's got to the point where the opportunity for improvisation has been minimized. Our characters

are still able to use their language and feelings, but the space we provide them with is very limited. We determine how the

scene should progress, and also whether there should be breaks within the scene. It's generally true to say we've never stuck

so closely to a screenplay before. Probably that comes across as well.

Over four films, if Babooska is included as well, you have created a universe which is clearly interconnected, and you also create gentle, playful associations:

the table where Tairo is sitting with Asia (the little girl from La Pivellina), the brief appearances of Patti and Walter (the protagonists of the last two films). Wendy is reminiscent of Babooska. What's

your general attitude towards the independence of each separate project and conscious interconnection between the films?

TIZZA COVI: It's a balancing act, a very slow, tentative process. We cut and edit chronologically. The exception is that I start editing

by working on the end and the beginning. That gives me greater security. When these two poles have been established you can

move around more easily with the smaller steps. Getting the beginning just right turned out to be particularly difficult in

the case of Mister Universo. But then the editing process becomes more relaxed and gains its own momentum. We had a lot of material for the beginning,

but balancing was harder than we had expected. This fragmentary working approach that we've adopted entails a huge challenge,

which is to ensure that the attention of the audience isn't dissipated.

Mister Universo is dedicated to all the people who have lost their jobs due to the digitalization of film. The demise of a declining craft.

How have production conditions changed for you, since you still work with analogue film stock? The chimpanzee in the film

is a witness to a different world of cinema.

TIZZA COVI: The old female chimpanzee Lola, who worked with great directors like Fellini, really is a witness to a lost world of cinema

that will never exist in that form again. We use a copying facility in Rome where great Italian films were created decades

ago, and we were shown the room where the negative cutters used to sit. There are at least 40 workplaces, and all of them

are empty now. It's hard to imagine what has been lost in terms of qualification and passion.

RAINER FRIMMEL: Huge numbers of copying facilities all around the world have closed down over the last few years because of the digitalization

of the cinema. That doesn't just mean the jobs have been lost, but that knowledge you can only obtain by experience has been

lost forever. A few analogue copying facilities will survive. Maybe one or two in Italy will survive. Maybe one in Germany.

And archive copies will still be created on celluloid for a long time.

TIZZA COVI: But the days of the great celluloid cinema are definitely over.

What consequences do you see from this development?

RAINER FRIMMEL: We still intend to film our next projects on analogue stock. Mister Universo was the fifth analogue film we made; we bought up a lot of old film stock from Fuji. But now Fuji doesn’t make any film

stock. Our next film will be on Kodak. Analogue film is simply the medium which corresponds best to our mode of working.

So will you stick to the same medium and the same environment for your next project?

TIZZA COVI: It seems to us that with Babooska, La Pivellina, The Shine of Day and Mister Universo we've portrayed this world enough.

RAINER FRIMMEL: The fact that the search in Mister Universo ends up being successful perhaps mirrors our own artistic searching and finding. Now we can concentrate on something different.

TIZZA COVI: After all, there are plenty of universes.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

July 2016

Translation: Charles Osborne