When Julia and her friends head to a Croatian party island to celebrate graduating from high school and enjoy life for one

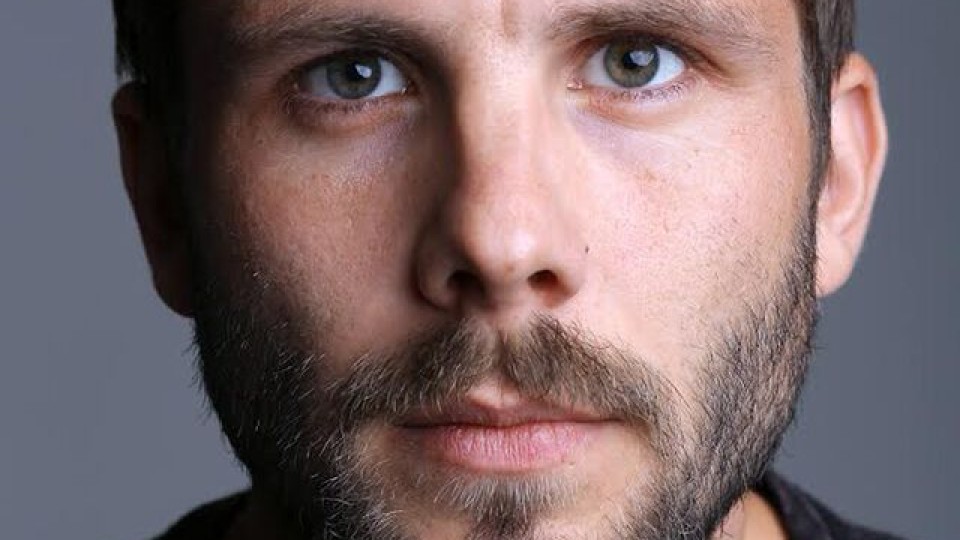

carefree summer, Dominik Hartl confronts them with a brutal avenger in the teen slasher movie PARTY HARD, DIE YOUNG putting a grim and dramatic end to their happy-go-lucky antics.

PARTY HARD, DIE YOUNG is your third full-length feature film. After a coming of age drama, Beautiful Girl, and a winter excursion through the zombie genre with Attack of the Lederhosenzombies, you have plunged back into the horror genre. Is the attraction of portraying emotions within a genre also associated with

the craftsmanship involved?

DOMINIK HARTL: It is certainly connected with the fact that I very much enjoy watching genre films. The craftsmanship aspect, for me, is

that in both the technical and the dramaturgical sense you can try out little things. The other thing I enjoy is having the

opportunity to trigger immediate reactions from the audience. People get scared, they get a shock; they go along with you

– or they don't. It's more about gut feelings.

This was the first time you didn’t write the film script yourself; how did that affect your work as a director?

DOMINIK HARTL: It's simpler at the beginning, because you don't have to start from a blank page, and at the same time you have an outside

perspective on the material. On the other hand, you have to struggle more to introduce some features. The first time I read

the script I immediately saw certain images. What becomes really interesting is when there's a horror scene or a stunt scene,

and you think about the best way to interpret it. One of the challenges was to set the story in a certain location, especially

since we shifted the action from Turkey to Croatia, and the script had been constructed around a particular feeling for that

place. The final major revision, which was definitely the most exhausting for me, was to produce a version of the script that

was feasible from a practical, technical perspective. It had to be shortened a lot, and you need a very sensitive approach

there, so you don't mutilate the original story.

In 2006 Andreas Prochaska pioneered the modern Austrian horror film with Dead in 3 Days, and that story is also set against the background of high school graduation celebrations. Why is that moment in a person's

life so appropriate for a horror film?

DOMINIK HARTL: Actually, I talked to Andreas Prochaska in the run-up to this film. I think leaving high school is a turning point in a young

person's life: it's a time of growing up and becoming independent, and it's also a time when friendships can break apart.

It's a phase in life that most audiences can relate to. I don't see any particular association with the slasher genre; I think

in general it's an interesting period when lots of things solidify from a coming-of-age perspective, which is also very relevant

there.

A holiday which is essentially a constant party for 5000 high school graduates who (are allowed to) let themselves go completely

– that's really a horror scenario in itself. How did you personally plunge into this world of mega-parties in order to create

an authentic portrait?

DOMINIK HARTL: The summer before we shot the film the production team sent me to Turkey for a week’s research. I was a bit nervous about

the mass atmosphere – I thought it might be terrible – but in the end it was a very positive experience. I'd imagined it would

all be brawling hordes, but it really wasn't like that. People were partying pretty hard, but it wasn't as wild as I had feared.

I think that's partly because the people were 18, straight out of school, and they did listen to the organizers. In fact I

started to feel we’d have to exaggerate some things a little: a girl would never have bared her breasts there. I think when

my generation partied after high school we were a bit wilder than the people I saw. My impression is that unfortunately social

media has prompted a degree of self-control and self-censorship. These days if someone pukes in a corner, the next day there'll

be a picture of it on the Internet.

I imagine you had to film during real graduation parties in order to get authentic footage of mass scenes. How did that work

out in practice?

DOMINIK HARTL: The noise level is one of the biggest challenges. There were 80 of us on the set, so communicating was pretty difficult.

We filmed all the parties on location, because we would never have been able to get such a large number of extras together.

For the party scenes the cameraman, Thomas Kiennast, and I worked out a concept that we applied to the whole shoot. The traditional

approach wouldn't have been feasible, because we had to adapt to things that were actually happening at that moment. We developed

a lighting concept that worked in all directions, and we had people sitting in various places who operated the lights whenever

the camera moved towards them. The second aspect was the music. We had agreed with the DJs that when we were filming they

would stick to a constant BPM, so the tempo wouldn't vary for the editing. What we wanted were scenes where the action included

the crowd around the actors. The basic procedure was that we would send our actors into a group of extras who formed the first

wall, and among them there would be someone from the team with an in-ear microphone passing on instructions. In a way it was

like filming on a theatre stage: Thomas went into the action with his camera and reacted wherever it was interesting. For

the actors it meant they always had to be completely present, because they could be on camera at any moment.

A crucial dramaturgical element in any story about 18-year-olds is their relationship with social media. And that's something

which clearly changes very quickly. How did you manage to integrate accurate user behaviour into the plot and the actual filming?

DOMINIK HARTL: That certainly was difficult. Just recently, after the film was released in Austria, we got feedback from young people indicating

that we did a pretty good job. I think that's partly because we left it a bit vague. At the moment Snapchat and Instagram

are popular, while this age group has really turned its back on Facebook. The film plays with the trick of the Snapchat photograph

that deletes itself. Obviously there isn't any established way of handling this on film yet. Maybe there won't ever be one.

And featuring it in the film involved a whole range of aesthetic decisions, from the app you use to the colours. We tried

to keep things very simple, to avoid the risk of being very fashionable now and looking ridiculous in three years’ time.

You mention colour, and that raises another issue of considerable importance. On the one hand the summer and the holiday atmosphere

call for bright, intense colours, but you also have the huge spectacle of parties at night, with that lighting. How did you

and your cameraman Thomas Kiennast approach this challenge?

DOMINIK HARTL: The colour concept doesn't only relate to the camera department. We started working on a lighting and colour concept at a

very early stage with the costume, set design and camera departments, and we very quickly settled on our approach. We wanted

to use contrast colours, such as magenta/blue, and completely leave out yellow. Yellow only features in the murderer’s mask

and the costumes of the main actress. We wanted to exert control here in a very subconscious way. The lighting concept is

dominated to a very great extent by the 1980s, and by contemporary music videos which are themselves largely influenced by

the 80s. Especially the glaring colours. I felt it was important to accentuate the location, a very appealing place. Thomas

is the right person to do this, because he knows exactly how to create this feeling of opulence in the visual language he

uses.

From the perspective of directing the film, was it more enjoyable to work with this opulence in comparison with Attack of the Lederhosenzombies, where to a great extent you had to take into account subsequent SFX effects during the shooting?

DOMINIK HARTL: What I really enjoyed about shooting this film was the fact that we broke up the staging and the actual filming. The idea

was simply to go into a situation with the camera without telling anyone in advance exactly how he should move from A to B.

I'd really like to film everything that way in future. But I have to say it’s only possible with a very competent team. I'm

thinking of our focus pullers, who were standing at the monitors – sometimes up to 30 metres away from the camera – and had

to estimate the focal distance that way. If you want to work with actors in such a free way, you have to have the technology

to match it.

The editing of the film is very fragmentary: to what extent is that also due to the music in the film?

DOMINIK HARTL: The fragmentary editing is connected to our way of filming, where we didn't necessarily prioritise continuity or axes. It

was also an aesthetic statement, though. We wanted a certain subversive feel; we really didn't want to come across as too

mainstream. It's all connected with the zeitgeist of a generation that isn't familiar with film semiology, a generation that

– unlike mine – isn't influenced by music videos either. Instead, their visual standards are much more related to amateur

YouTube videos.

Where will this experience take you next?

DOMINIK HARTL: My first two films didn't do very well in Austrian cinemas. For me personally this film was very important, and it was a

great relief to see that it has done well with the most difficult audience: young people, who go to multiplexes all over the

country and aren’t specially interested in films just because they’re made in Austria. If this hadn't worked out, I wouldn't

have made any further efforts to reach that audience. At the same time I've come to realise that the material I work on these

days is heading more in a personal direction. So I wouldn't exclude the horror genre in future, but I do feel like going into

some depth again.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

May 2018