America is always waiting to be rediscovered. In his essay film HENRY FONDA FOR PRESIDENT, on the works of the eminent Hollywood star, Alexander Horwath embarks on a wide-ranging journey of exploration into well-known

and lesser-known territories. He interweaves the family history of the Fondas, the body of work created by one of their most

prolific offspring and excerpts from the past and present of the United States, creating a polyphonic and at the same time

very personal homage to a multifaceted country and the uncountable versions of itself that emerge from the dream factory.

Your "acquaintance" with Henry Fonda began in Paris on a trip with your parents. Is he, in particular, a personality who laid

the foundation of your socialization in film history, your love of cinema?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: That was more my mother’s role. Fonda – like his daughter Jane, who I was deeply infatuated with at the age of 14 – was one

of the actors who touched me at a very early age. But the more fundamental influence was my mother's penchant for theatre,

cinema and literature – and for actors, especially from German, French and English-speaking countries. My first love for the

cinema was, as with many people, focused on certain actors. For my mother that meant Gregory Peck, for example, Oskar Werner

or Yves Montand, while for me it was the Fondas, Barbara Stanwyck, Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin... I've always tried to preserve

this approach to cinema. Later, I didn't just want to exchange it for the more "adult" and classic cinephile perspective –

the idea that it’s the directors who embody true authorship in film. To this day, I am of the opinion that when it comes to

the complicated interplay of forces in filmmaking and cinema culture, some "acteurs" can also have the function of "auteurs".

This is one of the central speculations in my film.

You headed the Vienna International Film Festival for five years and the Film Museum for sixteen years, which involves a very

specific appreciation of filmmaking around the world and its outstanding creations. Considering the wealth of your knowledge,

how is it possible to choose a single personality?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: All that other work – the writing, curating and organizing – necessarily means keeping "the whole field" in mind, at least

as an illusion. But every individual act, whether it's deciding on a film series, writing a certain essay, or joining and

running an institution, is still based on personal motivation. The question is how much one can become aware of one's own

motives, in view of the prevailing formats and expectations that are constantly imposed on these activities from outside.

I think I've avoided alienated or standardized work relatively well, because I've always kept that tension in mind. Now, with

this film, it was rather easy. There were no expectations from outside anyway. And the form of the essay film was an obvious

choice, because it is one of my preferences in film history – and because I myself come from "writing and speaking". I like

the unpredictability that essay films often possessed before it became a fashionable genre at art universities... And the

double subject of America and Fonda was the only material that I thought was somehow waiting for me. A subject nobody else

would approach in the same way. In a culture of dogmatism, Fonda's penchant for doubt has always been appealing to me.

Were you pre-occupied by particular thoughts, desires and considerations before you arrived at the decision to create a work

for the big screen yourself?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: I knew this leap would only be meaningful for me if it took place in an intimate and independent setting – and it would be

fine if that meant taking a little longer about it. I dared to make the film because it was possible to do so together with

Michael Palm and Regina Schlagnitweit. Michael is not only the experienced professional in the team, as editor, cameraman

and sound expert, but has also been a good friend for decades. And Regina has been my partner in love and crime for just as

long, which means she is also the most important corrective factor in terms of aesthetic choices and how to communicate ideas.

The fact that the producers, Irene Höfer and Ralph Wieser, allowed us this freedom and intimacy was very crucial too, of course.

The complex, fascinating and often surprising interlinking of Henry Fonda's biography and the Fondas’ family history must

have been backed up by profound and wide-ranging research. What were the starting points in this actor's career that provided

the impetus for this multifaceted analysis?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: The key point is that, more than perhaps any other film star, he makes his country legible in such a rich way – also due

to biographical coincidence. This was confirmed more and more during the research and filming. I wanted to make a film about

America, from a perspective that wasn't too hackneyed, and at the same time a film about Fonda – but not a linear biopic about

a celebrated "genius". This was only possible because of the way Fonda's traces and connections develop: he gives us a view

of the American condition that is broad and at the same time precise at particular moments. He does this firstly through the

major films that he put his stamp on, historical ones like Young Mr. Lincoln and Fort Apache as well as topical ones like The Grapes of Wrath and Fail Safe. Then by virtue of his particular family history: the early migration of the Fondas from Holland to America, later from the

East to the Midwest, and from there to New York City and California. Even in his own life, his worldview, and in his style

of acting, there are powerful echoes of issues that have defined America's political history, including the contrast with

his own "children of ‘68". You could certainly unpick the USA along the lines of a different star persona, but I feel that

the sheer density and variety of sources, places and coincidences in his case make him special.

Which films made you aware of the extent to which Henry Fonda's artistic work is also a political act, and even the films

created by the dream factory can’t be apolitical?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: Fonda himself would be very skeptical about this thesis. Outwardly, he always emphasized the distance between the roles he

played and his own life. But of course, everything is political, and that applies even more to the structures, products and

effects of the entertainment industry. The political forces that shape a society can be seen not only in the official locations

but also – or especially – in that society's "dream life", as Norman Mailer called it, "a subterranean river of untapped,

ferocious, lonely and romantic desires". In the 20th century, we learned a lot about these imaginations from the cinema. My

game of contrasts with Ronald Reagan and Fonda refers back to that.

You work in interdependencies but even more so in layers. One of these, which runs through the entire film, is the interview

over several hours that Henry Fonda gave to journalist Lawrence Grobel a year before his death. Detailed conversations at

the end of a life have something of a legacy and can also be an opportunity to frame the image of oneself. What effect did

this interview, perceived as a whole, have on you? How is it available to posterity? How did it become the basic motif of

this multi-layered composition?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: I got in touch with Mr. Grobel and was extremely happy to hear that the twelve-hour tape of the interview he conducted with

Fonda over several days in the summer of 1981 still existed. We acquired it and digitized it – and I sat over the transcription

for a couple of months... Fonda was rather taciturn; he never wanted to be the center of attention in private and was highly

critical of himself. During that period, he submitted to his family's wish that he should leave something autobiographical.

In the year of the interview, a book was also published, FONDA: MY LIFE As told to Howard Teichmann. In this sense, the legacy

and framing aspect probably plays a role. But he doesn't sound like it in the interview – Fonda is often very direct and wittily

grumpy when it comes to people he loves or hates. He refuses to answer a lot of the analytical questions, and he prefers to

talk about things outside his films and the roles he played. These tapes were very productive because Fonda implicitly answered

almost all of my questions – and also because of the texture of this recording. The old, brittle voice, the birds in the garden,

his sneezing...

Historical sources and facts, film excerpts, audio recordings, archive material from TV... the research work for HENRY FONDA

FOR PRESIDENT seems to have been more than complex. Where did this work begin to take shape?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: During the many U.S. trips that Regina and I have been taking since the late 1980s – that would be one answer. Because that’s

where you learn to redefine the relationship between cinema and on-site experience. But everything became really dense during

the project development phase, in 2018/19 – the very deep research, the immersion in potential Fonda material and in certain

moments and figures of U.S. history. We often spent very enjoyable weeks roaming through "ephemeral" film history, including

advertising and propaganda films, talk shows and amateur films. And then there were months when I was completely absorbed

by Margaret Fuller's or Hannah Arendt's writings, Lincoln’s speeches, recent essays on political theory and the storming of

the Capitol in 2021.

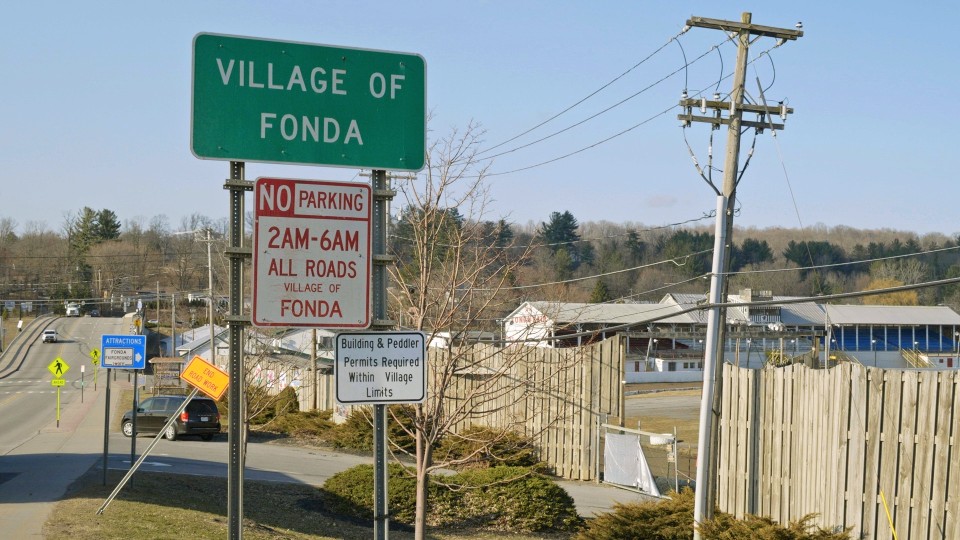

HENRY FONDA FOR PRESIDENT takes us on a journey from the 17th century to the USA of the Reagan years. Where did your historical

research take you? What prompted you to counterpoise these historical sites with images from the present? Was it also your

aim there to bridge the gap between Henry Fonda's death in 1982 and the present day?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: Historical films and TV shows often put on such an "immersive" act. The audience is led to identify with a first person singular

view of the era, "as it felt back then". But of course these are all re-enactments, it’s a mise-en-scène. I wanted to include

the locations in the present-day U.S. that are relevant to Fonda because it's a film and a perspective from today. The temporal

distance to the historical complexes that the film deals with is abundantly clear. On the other hand, I specifically looked

for sites where, like in the movies, actual stagings of historical reality takes place – pageants, History parks and fairs,

museums and plain roadside memorials... And then there are graves and crime scenes, an abandoned sanatorium, a former U.S.

Air Force base – places that only "re-enact" something in the context of Fonda's biography and filmography. That way, today's

USA is present in this way, as a layer on top of other layers and traces, but I have omitted the current headlines about the

U.S. – hopefully they will resonate by themselves. Many of the "historical scenes" as well as Fonda’s life and work now appear

almost haunted by these current questions.

You say at the beginning that on your trip to Paris you saw The Wrong Man, Once Upon a Time in the West and The Grapes of Wrath. So does that mean you saw three emblematic films which delineate very important stages of his career? What considerations

go into the definitive selection of your film excerpts? To what extent were you attempting to do justice to Henry Fonda as

an actor, in terms of his presence on screen and his choice of roles?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: The three films are definitely part of his core oeuvre, but since then I've seen about 70 of his roughly 100 films, and one

way or another I've taken about 40 of them into consideration during this work. The excerpts were then selected exclusively

on the basis of the arguments I pursue in the film. This applies to Fonda's style of acting, but even more so to the persona

known as "Henry Fonda", whose crypto authorship of a certain narrative – or counter-narrative – of America I’m trying to suggest.

A potential president who would have preferred to remain anonymous, a "nobody" who represents a multitude of other nameless

or forgotten people and not a "well-rounded", stable identity. Someone who wants his ashes to be scattered in the sea.

In your voice-over, you define the technique of chiaroscuro as the method of grasping the space between light and dark. The

selected film excerpts from Henry Fonda's black & white film era are a captivating exploration of this game of contrasts.

Was this formal aspect a criterion in the selection of some excerpts? What does this interplay of light and dark reflect,

with reference to your view of Henry Fonda, and also to developments in American society?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: The visual aesthetics weren’t decisive in the choice of excerpts, though it's a nice side effect. I was mainly interested

in the ideological black-and-white discourse about America. The contradictory, malleable zones between "very light" and "very

dark" are far more realistic and interesting – at least, that's how my own interest in America came about. And as far as the

Fonda persona is concerned, there is his gaze which is simultaneously present and absent – and there are his actions which

are guided just as much by the sense of possibility as by a sense of reality. They often refer to utopian concepts or "lost

causes" in history. What do we say to the dead?" he says at one point, in Fail Safe. That, too, is part of the chiaroscuro.

One of the major themes that concerns you during this obstacle course is the history and interpretations of the American concept

of democracy. Could this be seen as a central issue?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: It's certainly one of the main lines in the film. "Democracy is not a fair-weather event," wrote the philosopher Rainer Forst.

It is not a question of avoiding disputes but of enduring and negotiating fundamentally contentious issues. In contrast, playing

games like "Make America Great Again" – or "The People’s Chancellor", as the current populist slogan goes in Austria – points

towards authoritarianism and ethnic nationalism. However, they are not an invention of our time, which is why the film also

looks back at the 1830s, for example. Fonda's young Mr. Lincoln is surrounded by figures like Andrew Jackson, a super-racist

president, and Margaret Fuller, a writer who dealt thoroughly with women's political participation, with slavery and with

the indigenous peoples whose existence was endangered by Jackson's policies as never before. It's about demagogy versus deliberation,

concepts of "strength" and "weakness", mob justice versus the rule of law. In Fonda's cinema, two rough ideas of the United

States of America compete with each other. An America that historically predates the actual state, the United States, and

continues to make waves as an ideological "primordial soup". A mythical "deep state", founded on blood and exclusion. The

United States, the republic, the rule of law, must constantly and untiringly assert itself against that.

What strikes me as a second crucial theme is a reflection on images of masculinity, and Henry Fonda was always the incarnation

of that as an actor; interestingly, references to periods of history with matriarchal structures appear several times in your

historical analysis. Does this also resonate with the extent to which today's America is a result of the exercise of power

by white men, and to which the history of this country could have taken a different course?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: Fonda was certainly not a feminist. But he invites a critique of the authoritarian character and male triumphalism – especially

where he himself embodies such "armoured" types – for example, as Colonel Thursday in Fort Apache. By means of the numerous satellite characters that appear in the film I also wanted to pick up on Fonda's critical potential,

his ability – or his urge – to doubt, even regarding the option of taking on the role of a politician himself. Fonda splits

a bit into these other characters, into (hi)stories of the USA that have long been covered up by the narrative of the "great

white male democracy of Mount Rushmore". This includes people like the black Air Force pilot and exile Virgil Richardson or

the Mohawk woman Tekakwitha, who perished as a Jesuit, but also a terrible reactionary like General Curtis LeMay. Such evocations

of counter-histories and previously neglected protagonists are not new anymore, of course, but I hope that some of them remain

unpredictable for the viewer...

HENRY FONDA FOR PRESIDENT is the result of an enormous amount of montage work. Can you tell us about the main stages and decisions?

Working with different levels, which you have already mentioned, is interesting. Your own eloquent personal analysis adds

another layer to the film. How and when did this text come about, so it would be in harmony with the montage? Why was it important

for you to give this film your personal voice?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: An initial text, which already connected to various film quotations that I had in mind, turned into a dialogue with the Fonda

tapes from 1981. His voice, his statements transformed the text, sometimes overturned it. The two shoots brought completely

new options and many satellite figures into play. What we experienced on site determined again and again where the journey

of text and image would continue... Regina's archival discoveries would also lead to such detours. In any case, what had begun

as a "soliloquy" and a dialogue, quickly turned into a network of voices, which we were somehow able to keep under control

thanks to Michael's experience and his editorial skills. At least I hope so! A lot of sidetracks have been eliminated, actually

– the film was originally five hours long. Some of the things that were left out, such as the "Henry F./Jean-Luc Godard/Jane

F." complex, or the three days of shooting at the Fonda Fair with roaring engines and roaring cattle, donkeys, and sheep,

would even be suitable for separate satellite films... In any case, the text, as interwoven with images and other sounds,

changed constantly and meticulously – sometimes even in dialogue with Peter Waugh, who translated everything into English

for the subtitles. As far as the voice-over is concerned, we didn't like the idea of having a slick "professional speaker"

running through my text. At the same time, I was unsure whether my own voice was any good for this purpose. Ruth Beckermann

helped me over the threshold with her insistence: "You HAVE to say it yourself!!"

Do you intend to create a multifaceted portrait of an outstanding artistic personality in this work, or more to offer a form

of historiography, on the basis of an important filmography, and thus to show how much MORE cinema is than telling stories

and destinies that allow people to immerse themselves briefly in another world?

ALEXANDER HORWATH: Hopefully the latter. But it would be nice if, along the way, the former could also become tangible. Basically, I aimed at

three things: America is the subject or force field of the film; questioning the forms of historical perception is my central

impulse; and Henry Fonda – as a person and persona – was and is the endlessly fascinating tool that helped and still helps

me in trying to address these two aspects. "I don't feel I have good answers to anything," he says in the film – but he's

wrong.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

January 2024

Translation: Charles Osborne