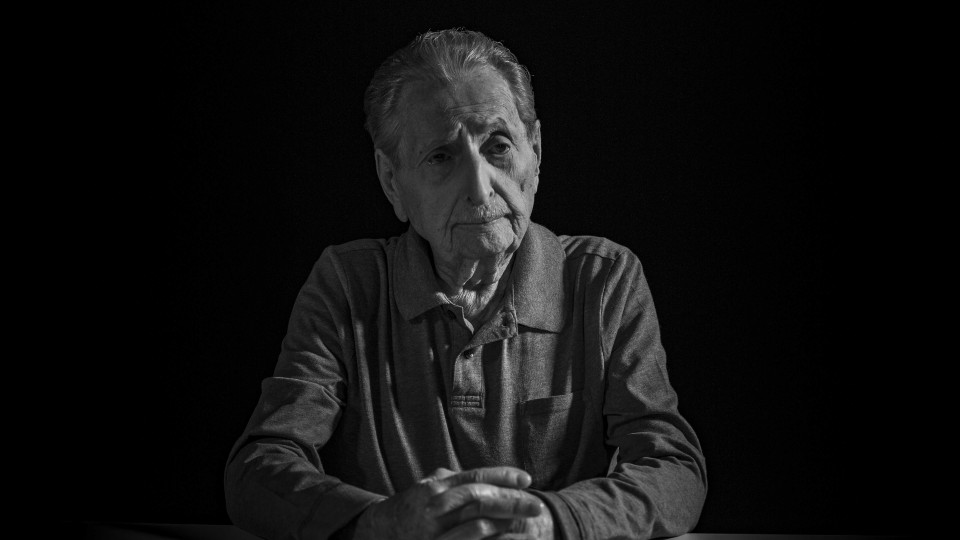

Marko Feingold (1913 – 2019) was arrested soon after the Nazis seized power and survived six years during the reign of terror

in various concentration camps. After the liberation he built up a new existence for himself in Austria, and throughout his

long life he never tired of raising his voice to warn against forgetting or denying that period. At the age of 105 he gave

an exclusive interview to the filmmakers Christian Krönes, Florian Weigensamer, Christian Kermer and Roland Schrotthofer;

in the documentary film A Jewish Life his fearless determination to fight on and survive refuses to be silenced.

In 2016 you released A German Life, featuring conversations you recorded with the 105-year-old Brunhilde Pomsel. Your protagonist in A Jewish Life, Marko Feingold,

was the same age when you filmed him. How did it come about that you have created a small series with A German Life, A Jewish Life and the project A Boy’s Life?

CHRISTIAN KRÖNES: In the back of our minds we were always aiming for a series of films featuring the last contemporary witnesses, but when

the protagonists are so elderly naturally it is a race against time. There was broad support from the very start for A Jewish Life, but it was completely different with the development of A German Life. Many funding partners were scared by the idea of a film portrait of Brunhilde Pomsel, Joseph Goebbels’ former secretary.

Which made it all the more pleasing to experience the success of the film, with numerous festival invitations, selection for

the European Film Award, Oscar qualification and cinematic releases in 13 countries.

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: The idea of making films from different perspectives also appeals to us. In Brunhilde Pomsel we had a classic collaborator,

a protagonist who profited from the situation. Marko Feingold is a victim of National Socialism. He was arrested as early

as 1939, and he spent virtually the whole period in concentration camps, until his liberation in 1945. At the moment we’re

working on a third film, A Boy’s Life, with a protagonist who was sent to a concentration camp at the age of 8, so we can also shed light on this period from the

perspective of a child. To get an overall picture it would also be interesting to feature a resistance fighter and a perpetrator.

We haven’t found anybody yet for those projects: the last contemporary witnesses are disappearing.

Marko Feingold says himself: “The memories are the meaning of my life today.” He seems to have become a real memory worker

who never tired of describing his experiences. In contrast, Brunhilde Pomsel spoke about her experiences in public for the

first time in your film. In what way did the conversations with Marko Feingold place different demands on you?

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: He was a memory worker, that’s completely right. Day and night. During the shoot we had planned a few days when he could

rest. But he arranged to give talks in schools on those dates. Telling his story was the whole purpose of his life, and perhaps

that’s also what helped him reach such a great age. The difficulty that arises when somebody constantly repeats his story,

and has to answer very similar questions, is that certain formulations are repeated. Breaking through that in the long interview

we conducted, in an attempt to get deeper and escape from certain narrative patterns, was quite a challenge. He knew exactly

which things he wanted to communicate, and of course his personal aims were in the foreground for him. But there were also

moments where we were interested in something else. Getting those answers wasn’t always easy: he could be as stubborn as a

mule.

CHRISTIAN KRÖNES: I can also imagine that those narrative patterns gave him the distance necessary for him to be able to speak about what he’d

experienced in the first place. Questioning him further, in an attempt to get deeper, can of course be very painful. Being

able to describe certain things again and again probably entails establishing a certain distance for yourself.

Marko Feingold spent six years of his life in concentration camps. He describes his childhood and younger years in detail

but talks less about his experiences in the camps. How far did you dictate the direction of the conversations, and how far

did you let yourself be led by him? Was it also important for you to focus on the period before the Nazis seized power? On

the way people underestimated what was looming on the horizon?

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: At times Herr Feingold definitely guided us. Whether a conversation began to flow depended on his mood as well. The most important

thing was to take enough time. We studied his biography closely beforehand, and we had a rough guideline for the subject areas.

Of course that also involved exploring the creeping social changes before the Nazis seized power. After all, Marko Feingold

and his brother lived in Italy after 1932 and were successful businessmen there; they certainly underestimated the political

changes.

CHRISTIAN KRÖNES: I was particularly moved by all the fateful moments he experienced, by the way particular decisions, or wrong decisions,

could have fatal results. When he came back to Austria from Italy in 1938 with his brother it was more or less by chance:

their passports had expired and had to be extended. It was a crucial period, just before the Anschluss, when Germany annexed Austria – which he experienced as an eyewitness on 12 March. He used to say he wouldn’t have been able

to contradict the later Austrian version of history – which claimed that Germany had invaded Austria – if he hadn’t been standing

with the welcoming crowds in Heldenplatz. He experienced at first hand the way Vienna transformed itself overnight. Just

a few days later he and his brother were arrested for the first time. When they were released they fled to Czechoslovakia

using invalid documents, they were deported to Poland, and then they returned to Prague as the noose tightened around their

necks. For a long period they just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, until they were arrested again and

finally sent to Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: It seems to me that the question of how things could have got to that stage is crucial, with the previous history in Vienna

and the dormant anti-Semitism that was always present. Another vital point is the political indifference of the general population;

Feingold addresses that issue and doesn’t exempt himself from this charge. He also stumbled into that trap, which is an important

point that can teach us a lot today. Political indifference can very quickly lead people in a direction that nobody wants

to go.

CHRISTIAN KRÖNES: Alongside all the blows of fate, Marko Feingold also had incredible fortune to survive that period. It’s possible that the

crucial factor in his good fortune during the disastrous time was that he grew up in the Prater area of Vienna. Being socialised

in the typical underworld surrounding the Prater funfair at that time, having to assert himself as a child and learning tricks

and strategies, must have helped him evaluate people more accurately. Probably the “school” of the Prater gave him the tools

he needed to survive his years in concentration camps.

What was the significance of his life after the war in your conversations with Marko Feingold?

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: He was an incredible fighter: if anybody attacked him, he would always launch a counter-attack. He simply refused to be put

down. The period immediately after the war was an important part of his life. He ran an aid centre in Salzburg for people

who had been liberated from the concentration camps. It became the point of contact for a huge number of refugees. In 1945/46

he helped about 100,000 Jews from all over Europe travel illegally across the Alps to Italy and on to Palestine. His diplomatic

skills were extremely helpful there. He organised a huge refugee operation, and he was rightly very proud of that. Today,

when you can be arrested for helping people who are drowning in the Mediterranean, he would be locked up for it. In those

days he was a hero, and he still is today.

CHRISTIAN KRÖNES: I think we have to be extremely grateful to him and all the others who stayed after the war. I’m also thinking of Simon Wiesenthal.

They both had plenty of opportunities to emigrate to Israel. But they made a very conscious decision to stay in Austria, to

keep memories alive and to raise their voices against denial and the attempt to gloss over what happened.

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: Marko Feingold regarded it as his right to stay here. He felt he was an Austrian. He refused to be intimidated, and wouldn’t

allow anyone to silence him, which was extremely uncomfortable for a lot of people over many decades.

Was it clear from the beginning that you would use the same approach to camera aesthetics as in A German Life?

CHRISTIAN KRÖNES: With A German Life we spent an incredible amount of time developing a timeless cinematic form for the film. I think that work paid off. A German Life, A Jewish Life and our third project A Boy’s Life are all shaped by the same black & white aesthetic. We always open with close-ups of the faces, which reflect the passing

of a century and incredible personal destinies. They are fascinating faces that you can look at for a very long time. At the

same time, the intention is to use these contemplative opening passages to get the audience in the mood for a very different

time level and the coming narratives.

The interview segments are structured, on the one hand by film extracts and also by quotations from abusive personal letters

Marko Feingold received. Was it very depressing for him that right up to the end of his life there were people who denied

the Nazi atrocities, and that many of them were very quickly integrated after the war and achieved high positions in society?

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: The letters encouraged us in our aim to reveal the anti-Semitism in the present day. We wanted to make people aware that

this elderly man received letters (mostly anonymous) right up to the end of his life with threats and abuse, and to convey

to audience that the film is not only about the past. No. There are still people who deny the Nazi atrocities. Marko Feingold

kept the letters. At first he would take them to the police, but they never did anything. The attitude of Austrian politics

and society towards the Holocaust definitely pained him a lot. And he waged war on the Socialist Party, which he left in the

end, because those people also accepted or remained silent about lots of things that happened. And after 1945 the same people

were in the same positions they had occupied before the war. I do think he felt betrayed by that. He didn’t take the letters

personally; he rose above them. He regarded those people as idiots who were trying in vain to intimidate him. He refused to

be frightened or to get worked up about it.

You have both focused on this theme for a long time, very intensively; where did Marko Feingold open up aspects of the subject

and provide you with new perspectives? What is Marko Feingold’s legacy for you personally?

FLORIAN WEIGENSAMER: I was fascinated by his character as a fighter. He isn’t just a voice of warning and a narrator and a victim. He remained

a fighter for the whole of his life, someone who wouldn’t submit to anybody, even though he’d had to endure so much. That

impressed me a lot.

CHRISTIAN KRÖNES: I think we’ve been greatly influenced by all our conversations and getting to know our protagonists better. I regard it as

our task, especially now that the warning voices of contemporary witnesses are slowly disappearing, to pass on their memories

and their stories.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

July 2021

Translation: Charles Osborne