At some point, Rebecca Hirneise had to get away. Far away from her family, where religion held the thoughts and lifestyle of children and adults alike in an oppressive straightjacket. Many years later, the desire for connection and understanding led her back to her Swabian hometown. In GOD BETWEEN US she records her attempts to clear away the mutual alienation in her own family circle, where there’s plenty of prayer but not much discussion.

In your first documentary, you combine the intimate issue of faith and religion with an exploration of your own family. It's tricky territory. Did you struggle for a long time about whether to say yes or no to your own film project?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: Yes, I did. An initial rapprochement developed from a series of talks. Everyone described of their own accord what their lives were all about. Religion was already very present, because my relatives actually talk about religion a lot. It's just that people don't like to discuss it. Telling the family that I wanted to discuss religion was far from easy. The objection immediately arose that the discussions would only lead to arguments. Despite their scepticism, I ultimately decided to stick with my idea.

You start the film with shots on a plane, apparently the start of the journey back to your family. Was the oppressive effect of religion the primary reason for your departure?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: The phone footage on the plane was the very first I shot for this film project. I was very excited and anxious. I tried to remember what it was like back then, when I saw my family more often. It felt like a trip back to a world I had already forgotten. I moved away from my hometown at some point, because I wanted new influences. But I hadn't seen my Christian family since much earlier than that – largely because of religion. So we became more and more estranged from each other. I especially couldn't stand the missionary work performed by my grandparents and some uncles and aunts. Not when I was a child, a teenager or an adult. I felt very constricted.

Religion seems to be a theme that unites but also divides your family. Which interpretations of religion clash in the family?

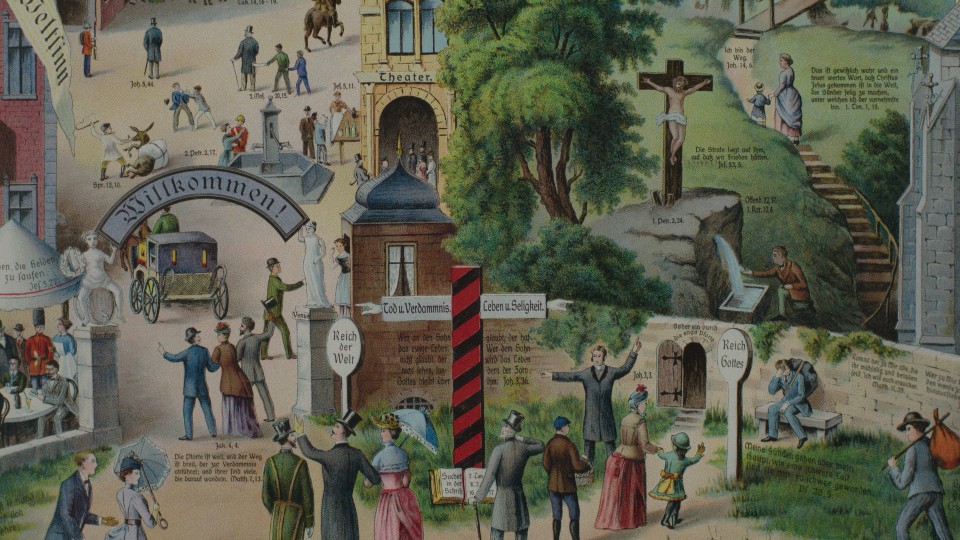

REBECCA HIRNEISE: That's a difficult question, and I don't really think it’s so very important as such. Everyone in my family is evangelical. My grandparents are Methodists, some family members go to both the Methodist and the normal local church, but there are also various small free churches that they attend from time to time. Once of my uncles even founded his own free church after a stay in America. I think watching the film will reveal more about how the different interpretations affect interpersonal relationships. And that, in my opinion, applies to many religions and different denominations. There really isn’t anything like a homogeneous landscape of faith. Even within the Methodist Church, there are divisions. In "our" church alone, there are two tendencies. One is more charismatic, where believers heal others with God's help or speak in tongues: "speaking in tongues" for charismatic Christians means that God speaks through a human body. The other direction is more conservative: it's more about the sermons and the right "piety". And even in this subdivision, everyone has a completely individual approach. It's like being able to cut out of the Bible with scissors what you don't like.

The impression arises that GOD BETWEEN US is a documentary project where very little was predictable. How did you find a structure?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: It really was difficult to plan it all. We had a lot of protagonists for a film of this length, but we wanted to get to know all of them closely and work out their conflicts with religion as precisely as possible. I had very long, intense conversations with the co-writer, Philipp Diettrich, and the cinematographer, Tilmann Rödiger, about how to structure the film. One big issue was how to best work out the main personal themes of my uncles and aunts during the filming. I initially focused a lot on the discussion groups. As a result, we got to know each other better, and the team also grew closer to the family. Whenever we came for discussions, we tried to film as much as possible of my relatives' everyday lives. We had to find a structure in various senses: writing, filming and editing. Especially in the editing room with Florian Kecht, a lot of things were created from scratch.

How did you find your settings outside of the conversations, where there are also great symbolic places, such as the swimming pool which acts as a baptismal font? Did a lot of things come together?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: We put a lot of thought into the various shooting situations. At the healing conference, the pool was the main topic of conversation when it came to baptism. A lot of people have been baptized in this pool. A healer, who regularly comes to my uncle's house to organize the Christian healing conferences, really wanted to baptize me, because the baptism of children doesn’t count in some circles. During the three-day conference, he repeatedly urged me to be baptized and constantly said in the group: "Rebecca is being baptized today." That wasn’t what I wanted; I had never asked for it. But he wouldn't give up. Almost everyone who was there had some sort of need, even a real compulsion, to persuade me to be baptized. It was a strange situation. Except my aunt didn't want to be baptized either, so we felt very connected. So the pool became more and more important for me personally, and I really wanted to go swimming in that pool. With my aunt – but without being baptized!

How did you discuss the camera work with Tilman Rödiger and at the same time find your place in the picture and off-screen, as director and protagonist at the same time?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: Sometimes I felt the need to film certain scenes myself. The scene with my aunt, who leaves the frame crying, is one of them. I would have found it intrusive to follow her with the camera. During one conversation I was actually so emotionally involved that I couldn't even look into the camera for a while. The way the shot drifts and shakes is also somehow a sign of my own instability and emotion in these moments. It was important to me that Tilmann was always there. I didn't want to shoot without him. Thanks to him, it was possible to master the balancing act between being a filmmaker and a family member on set. My own positioning in the shot and on the camera was a constant, changing question all the way through. I didn't really want to be filmed. But because of my double or triple role, at some point there was no longer a separation. So it happened that I appear on screen more and more.

Your view of the place where you filmed has something of a very neat little town. What were your thoughts on this?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: We shot in my hometown, Mühlacker. The landmark of Mühlacker is a transmission mast. There has always been a lot of missionary broadcasting in my family. My grandfather also grew up right next to the transmission mast and lived and worked there (as did his father). So initially the station had a symbolic meaning. This fell away in the course of the work, because it was more and more about interpersonal relationships. The town itself is in Swabia. Swabians always like to have everything neat and clean. One of the great Swabian life goals is to build a house and have a beautiful garden. It seemed interesting to me to have a shot of all the houses from above, because when I look at it, I think about the interpersonal relationships of the people living there. It has something of a model city that you peer down at. I wanted an image that could also be transferred to other small towns.

One interesting element is your grandfather's photo and film archive, which provided interesting input on a research level and also on a visual level. What did these images bring to the film?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: I've known my grandfather's archive since I was a child. I still had some images of it in my memory. For the film, I combed through the archive. One aspect that surprised me a lot was that my grandfather forbade his children to go to the cinema, but at the same time he made films himself and had an understanding and love for the medium. Despite that, he denied his children – and himself – access to the cinema, which I found somehow suspicious.

What is your personal conclusion?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: Working on this film gave me a greater understanding of spirituality. I may have become stronger through the whole process. I no longer sit at the table with my family without expressing myself. In the past, I just didn't say anything. It may be difficult for outsiders to comprehend what a huge step it was for me to tell my family that I am not a believer. The fact that communication is now possible certainly has something to do with my work on this film.

At the same time, my work hasn't really changed anything fundamental. I am less of a believer than before, and the people who did missionary work before continue to do so. We now understand each other's different positions better, but this subject is still very charged.

To what extent is your cinematic work an attempt to find a way together despite completely divergent attitudes? Does the concentrated focus on the family suggest a broader social level?

REBECCA HIRNEISE: It certainly was my aim to find a way together. I advocate conversation. It always takes you further, although not necessarily in the same direction. I hope the film can be applied to various social issues. For me, that’s always visible and possible. That's why I revealed as little as possible in the film about what religion it was. In my opinion, the pattern of faith and religion is completely transferable to other religions. The people I talked to could also be Jewish or Muslim. My hope is that people can connect with this film, no matter what religion they come from.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

Jänner 2024

Translation: Charles Osborne